Note: this is a cross-post from The Realignment Project. Follow us on Facebook!

Introduction:

As the third year of recession ends, the scale of the task of undoing the social and economic damage of the recession is now made plain. It is already well-known that 15 million Americans are officially unemployed, with another 15 million unofficially unemployed. But the scope of the recession goes far beyond their ranks - more than half of the U.S. labor force (55 percent) has “suffered a spell of unemployment, a cut in pay, a reduction in hours or have become involuntary part-time workers” since the recession began in December 2007.

The widespread nature of workers' declining fortunes, even if they have not suffered unemployment, explains why it is that one-third of U.S working families are now low-income (i.e, under 200% of poverty), one lost paycheck, one illness, or one accident away from disaster. But as I have noted before, the underlying illness of stagnant wages and a weak labor market have existed before - the one-third figure discussed above is only 7% higher than before the recession, and during the previous recovery in '02-05 we saw that figure increase, never falling below its 2007 level.

A rescue is deeply needed.

So how then do we bail out the labor market - to rescue American workers? Any such effort much rest on three pillars - increasing wages (both to restore the damage done by the recession and to go further) directly, creating a permanent mechanism for maintaining purchasing power through a more redistributive tax system, and (as should be no surprise) establishing a system of social protection that can truly shield workers from the effects of a recession.

Rebuilding Wages:

Long-term readers of The Realignment Project know that the through-line of my posts about economic and social policy is an argument about a long-term structural shift away from wages and labor costs and toward profits and capital that is leading to persistent weakness in labor demand, especially for jobs that pay a living wage. I believe that it is this shift and the weakness it creates that is the ultimate cause of wage stagnation.

What is the evidence for weakness in labor demand?

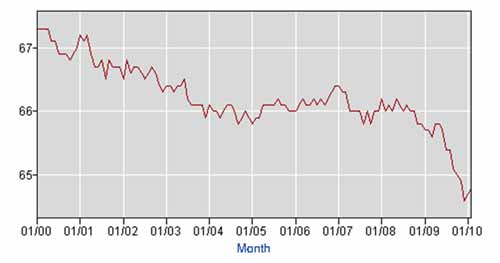

Recent years have shown a surprisingly soft labor market, to the extent that in the recovery from the last recession, the labor force participation rate actually declined and then flatlined, as we can see above. This is not normal. In the past, a recovery in a recession would tend to see participation rates rebound or increase as employer rehired their laid-off employees (as was the case in 1953, 1957, 1960, and so on) now we are seeing that economic recovery can no longer bring participation rates back - and at best hold things steady.

We can also see this softness in the fact that the broader U6 measure of unemployment (which includes discouraged workers, the marginally attached, and the underemployed) has been stubbornly high. Even during the white-hot labor market of 2000, when U3 fell to 4% and we actually started to see some wage growth for the first time in a long time, the U6 rate never fell below 6.8%. U6 stayed quite high throughout most of the early recovery in 2003-5, and stayed above 8% at the best of the most recent recovery. And in each business cycle, the nadir of unemployment ratchets upward - 7% in 2000, 8% in 2007, and I shudder to think what our new floor will become.

So we can see that the labor market has developed an enduring slackness, both in recessions and recoveries. My belief is that this is one of the major factors (and the dominant factor, to boot) that has caused wage growth to flat-lines. Workers are less likely to push for wage hikes when they know that they can be easily replaced, either by one of the unemployed, through increase in productivity, or through mechanization or offshoring, especially when the unions that normally foster wage growth are in decline. And what have we seen in American wages over the same period?

That red line tells the tale - thirty years of running in place and going nowhere. And this has, in turn, made our economic weaknesses even worse. When wages stagnate, wage-based consumption can’t grow fast enough to keep up with increasing production. Over the last decade, this was papered over with an artificially abundant supply of credit, making our economy more vulnerable to sudden credit crunches than it has been in the past. Hence, when a financial crisis paralyzes the credit supply, consumption drops faster than it would if consumption was more solidly based on wages; in turn, employers react to sharper declines in consumption with sharper increases in layoffs, creating a downwards spiral.

So how then, are we to begin to reverse this spiral?

A solution has to begin with a movement from our current national minimum wage, which remains $2.85 an hour short of its 1968 peak, arduous to raise through Congresses rarely attuned to the needs and interests of working people, and forever fighting a Sisyphean struggle against inflation, to a national living wage.

To call for this is not particularly novel in progressive circles; the more interesting question is where to draw that line. Many, such as former Labor Secretary Robert Reich have called for the minimum wage to be permanently indexed at 1/2 the median wage, out of an egalitarian principle which has a lot of merit. However, given a median wage of $15.95 an hour, this would result in an $8/hour minimum wage, not that different from its current level and just barely enough to keep a family of two out of poverty, let alone a family of three or four.

My own preference is to peg it back to its 1968 value of $10 an hour (ironically 1/2 the mean wage at the present time) and index that to inflation. At that level, a full time minimum wage job would be almost capable of supporting a family of four above the poverty line.

Rebuilding Purchasing Power:

Obviously, merely raising the minimum wage is not enough; it would directly help 3.6 million workers (or 5% of the workforce), and the ripple effects upward might reach as high as another 8.2 million workers (or 6.6% of the workforce), but that would still leave as much as 21.7% of the workforce still in need of assistance.

There is also the more philosophical question of how far minimum wage increases can get us to a just or fair distribution of productivity or profits, and the additional issue of how take-home wages are shaped by our taxation system. On the first question, let us observe that output per worker in the U.S was $105,000 a year in 2008, while the "median net compensation" per year is just $26,000 a year. Adopting a living wage as discussed above would shift about $5,500 a year back to the worker's side of the table for a broad swathe, but by no means all, of the workforce.

On the second question, let us note that despite the fact that the U.S has a strong historic legacy of progressive taxation (and that we do a pretty good job relative to European countries that rely more heavily on VAT taxes), our tax system remains broadly flat:

Thus, to the extent that we can make the tax system more progressive on the revenue side and more redistributive on the benefit side, the more we can ensure that the value of people's labor is recaptured and redistributed back to them. While it's fairly common among progressive policy wonks to argue that the EITC should be expanded into what is effectively a Guaranteed Annual Wage (as opposed to a Guaranteed Minimum Income), I think we have to both expand the scope of our ambitions and lift the level of our rhetoric.

On its own, the EITC runs the danger of becoming a Speenhamland for the 21st century; to transform it, we must begin with the understanding that the EITC should be more than a means of keeping people out of poverty - it should be explicitly tied to reducing inequality by linking the funding source to taxation on the top 1% of households, and explicitly paired with the minimum wage, so that the two rise in tandem.

Equally importantly, EITC cannot shoulder the burden of bailing out the working class by itself, any more than the minimum wage can. And here is where I diverge from my Progressive colleagues who have worked themselves into a fear over the payroll tax cut - the payroll tax is not the Progressive vision for Social Security. It was a pragmatic decision made at the time to get around the Supreme Court's narrow view on Federal authority and to politically protect the program through the establishment of the appearance of an insurance program. However, the dream of progressives - as enshrined in the Wagner-Murray-Dingell bill for the next fifty years - was to replace payroll tax revenues with General Fund revenues as an expression of national obligation for social security.

The payroll tax is our most regressive tax, and largely responsible for the flatness of the previous graph. While we should absolutely retain a symbolic link between contribution and eligibility for Social Security, there is no reason why making the payroll tax a progressive tax should not be at the heart of progressive tax policy. At one stroke, we would increase purchasing power, lower the cost of creating living wage jobs, create a strong disincentive against runaway executive compensation, and redistribute income on a grand scale.

Recreating Social Security:

While the above steps if enacted would result in a general increase in wages and real income for working people, which would in turn increase spending and employment, it's still the case that we do not have an effective safety net for preventing such swift declines in income and living standards in future recessions.

As I have argued before, we drastically need to rebuild our Social Security system into a universal and comprehensive institution for the protection of the entire population from major economic dangers. A big part of that will be restoring Unemployment Insurance to the point where it can actually protect against the sudden loss of income that comes with layoffs.

Ultimately, I think that a labor market bailout will have to face up to the task of dealing with the labor market directly rather than compensating for its weaknesses. A strong social insurance system and wage protection system will help, by giving workers more options and a feeling of security. However, there is in the end no alternative to creating a social insurance system for jobs to tighten the labor market for the long-term.

Comments

Comments are welcome

and a Happy New Year to everyone.

Median wage vs. average

It sure is and has been for some time. I think of all action items, jobs, work, labor is #1 and we have a GOP Congress that doesn't have their head screwed on right in terms of what creates jobs from what I can see in the political rhetoric. They are binary, tax cuts and deficits. Oops, with an overriding theme of doing whatever corporate lobbyists want them to do.

Did you see this post, Most of Us Are Have Nots?

It's loaded with graphs on wages, median wages, from the 2009 wage statistics data. It's much worse than one realizes because the average wage is pushed up by the super rich, they tip the scale. When one looks at the median wages and the wage bracket percentages, we're all poor, there really is not a U.S. middle class. Feel free to use any of these graphs and I also have the raw data for them for more graphs.

On the policy end, there is much more than just a minimum wage. I suggest a global minimum wage, and make it illegal for U.S. companies to not pay at least the U.S. minimum wage globally. If you want to do business with us, you cannot use slave labor.

Then, they need to curtail offshore outsourcing, use of guest workers. India, more than China, it's labor costs, pure arbitrage, that is their business model. This is because it's services, a heavy focus on technical labor, which is the most of the costs.

China, on the other hand, needs to be confronted on currency manipulation. That would help with overall costs, which is part of the reason U.S. corporations manufacture in China instead of the United States.

They need to reduce health care costs in the U.S., which as we know, they just gave the lobbyists what they wanted in the latest "health care bill" and it doesn't do anything to reform the system, which would reduce U.S. labor costs overall to provide them health insurance.

They also need to enforce labor laws. That's everything from sue for age discrimination, discrimination generally to stopping the hiring of illegal labor, to also looking at some of these new "bid on projects" websites, where companies are getting work for pennies per hour in reality. They are way below U.S. minimum wage, often for skilled labor and corporations, companies are manipulating 1099-misc. or independent contractors, i.e. small business, sole proprietorship, to avoid paying even minimum wage, never mind health benefits and so on.

They also need incentives for U.S. manufacturing and a strategy to rebuild the U.S. manufacturing base.

The laws against 1009-misc. workers are also horrific, causing 3rd party contract houses to be used, which simply take a huge cut out of that 1099-misc. worker's "pay".

Thanks for the data

That'll help in future installments.

Your focus on minimum wages,

Your focus on minimum wages, unemployment insurance, and so forth is understandable.

I do wonder just how effective these measures are in terms of rejuvenating the American economy.

Increasing the labor cost component of a workforce which is increasingly service based - and thus far less able to increase productivity - seems to be a much less effective tactic than reducing the cost component of standard of living.

And what is the largest component of standard of living? Housing, both rent and purchase/financing cost.

Having housing costs - which are over 1/3 of overall cost of living - drop 10% or more via removal of both bankster lobbied subsidies and massive negative equity loans will not only free up existing income, but also reduce cost of everything else.

I disagree

As our economy becomes less exportable, wages should rise.

Lowering costs is a limited strategy - since it'll have a backfire effect on employment in construction, materials production, etc.

Krugman wants a WPA like the FDR direct jobs program

Krugman wrote another editorial, pointing to the GDP multipliers for jobs growth leaving us with this crisis extrodinaire for some time. No kidding!

So, he's put forth again the idea of a WPA, or direct jobs program. I think we've been talking about some sort of direct jobs program since the start of this site.

Even worse, it's looking really worser on the political front, we need to cut through that FAUX/political noise which spins the crisis to be these corporate, super rich lobbyist agenda items as solutions.

People, I honestly don't think understand cause and effect on policies vs. jobs.

I saw that

It's quite important that Krugman and his ilk are becoming more friendly to direct job creation where before they were for vanilla demand management. It should help in the long-run if the center-left can get on the same page.

What an excellent analysis

Workforce participation, U6 analysis based on recessions, and CPI adjusted average hourly wages. You'd think that you were a very high level policy analyst providing the latest Medici the absolute best information. In a way your are but they need to read it.

What's the point of an economy, or a political entity, unless it works for all of those involved. It's not like the Middle Ages where people were blind to better options.

The mindless focus on quarterly earnings as a function of someone's bonus is a crime and the graft and corruption on top of that is a crime against the state. Time to clean up and look at the obvious problems and solutions with these factors at the front: a) What works for the people? b) Is it being done with intellectual and professional honesty?

Where will the stimulus for inclusive, honest government comes from? Will it be a big ank failure in 2nd or 3rd Q? Will it take 1000 dead birds falling on Wall Street (specifically) instead of Beebe Arkansas? Does a camel need to fit through the eye of a needle;

Whatever it takes, we need a radical shift for the better and soon. The failures are getting to be too harmful and also, they've become tedious. It's the same old same old from the usual cast of incompetent characters.

Michael Collins

that's why we are here

To help explain a math equation, an assumption and get people to be able to read a graph or two. If we can do it, then by golly, they can do it.

Good article Steve. Another

Good article Steve. Another benchmark would be to peg minimum wage at 10% of congressional salary of ($174,000), which divided by 2000 hour work year is $87. So $8.70 an hour, about where Washington State is as of the New Year ($8.67).

The "universal living wage" folks have an interesting idea, set minimum wage for each metro area based on housing costs x 3 (using HUD indexes). Some of them seem rather high, I guess you're still in Santa Barbara, which would be at $19.33/hr minimum versus Bakersfield, $11.96/hr.

http://universallivingwage.org/ulwformula.htm

Then again, the Australian minimum wage is $15/hr (US and Aus dollars at par currently). More than twice the US minimum wage and yet our capita income is 15% higher than Australia's ($46k vs. $39.9k).

As you can surely imagine, the Australian unemployment rate is catastrophic, from story earlier today:

The national unemployment rate in Australia now sits at 5.2, close to full employment, after more than 400,000 full-time jobs were created in the past year.

http://www.theaustralian.com.au/business/markets/stressed-labour-market-...

I blame the single payer healthcare system for their troubles. :o)

correction...

"and yet our [per] capita income is 15% higher than Australia's ($46k vs. $39.9k)."

I was comparing 2009 wages with current exchange rates, so the 15% differential is inaccurate. Exchange rates are a moving target, but sufficed to say, Australia's per capita income is similar to our own, we just share it (or not) differently.