Transcript: MiB: Jeff Chang, President and Co-Founder of Vest

The transcript from this week’s, MiB: Jeff Chang, President and Co-Founder of Vest, is below.

You can stream and download our full conversation, including any podcast extras, on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube (video), YouTube (audio), and Bloomberg. All of our earlier podcasts on your favorite pod hosts can be found here.

~~~

[00:00:16] Barry Ritholtz: On the latest Masters in Business podcast. I sit down with Jeff Chang. He’s co-founder and president of vest. They are a firm that specializes in defined outcome investing, buffered ETFs. They try and remove the uncertainty of outcomes of your investing by using options and derivatives to come up with very, very specific products. I thought our conversation was fascinating, and I think you will also, with no further ado, my podcast with Jeff Chang. Jeff Chang, welcome to Bloomberg.

[00:00:52] Jeff Chang: Great to be here, and thanks for having me. Oh, well

[00:00:54] Barry Ritholtz: Thank you so much for coming. I’m kind of always fascinated by people who have unusual or diverse backgrounds. You in particular US Naval Academy and then an MBA from Georgetown. Is that right? What, what was the original career plan?

[00:01:11] Jeff Chang: So, I grew up in Annapolis. The original career plan was to be, you know, be part of the Navy. And unfortunately, I got medically discharged for, for asthma and then, then decided to pursue more of a business path. And that’s what kind of led me to, to Georgetown. And then after Georgetown, I actually, right after, I actually always wanted to start my own company. Right. In fact, this is kind of a funny thing. Most people don’t know this. I’ve never actually said this. When I first started, I actually started a flat screen TV company in 2012, OEMing them from China. And do you remember back in the day, like flat screen TVs used to be like 25, 30,000.

[00:01:54] Barry Ritholtz: Oh yeah. When they first came out, they were crazy.

[00:01:55] Jeff Chang: Yeah. Yeah. So I was in DC selling those. In fact, I remember selling TVs to Reagan National Airport. So when you like, look at what terminal you are, back in the early two thousands. Wow. Those were Jeff Chang TVs that were there. No kidding. I think another client was Six Flags. Like when you, you

[00:02:13] Barry Ritholtz: The wait, how long the wait is.

[00:02:14] Jeff Chang: Yeah, yeah, exactly. Exactly. But then, you know, as TVs became further and further down, like I was like, Hey, that’s not the business I want to be in.

[00:02:21] Barry Ritholtz: So all commoditized, why do you want to be

[00:02:23] Jeff Chang: There? Yeah. It all commoditized. So I, it taught me a lot about starting a business on, you know, that and about life, is that I realized that I needed actual hard skills that that created a, a, you know, value add. And also the other component was I, I also realized that doing like accounting books, I didn’t pay too much attention in accounting. So I actually for six months went and studied for the CPA exam and took the CPA exam to be accounting, which was actually a twofold kind of reason. I think one of my mentors once told me is that like, hey, there, there is, for the better word, there’s fu money and FU skills. Right? Right. You don’t have that money. So make sure you’ve built skills in which you’re not always beholden to other people. And if you thought about it that, you know, the two guaranteed things in life is death and taxes. Right. And so in my head was I didn’t wanna be an undertaker, but I could take the CPA exam and assure that

[00:03:27] Barry Ritholtz: Participate in taxes wasn’t

[00:03:29] Jeff Chang: Exactly, exactly. So

[00:03:30] Barry Ritholtz: A growth industry.

[00:03:31] Jeff Chang: So that was the reason why I took the CPA exam was that like, Hey, I know I would never starve because, you know, after the failure of my first firm, I was like, Hey, there’s, you always have to have at least a safety net. And that also informed me that when I started a new company, accounting is actually extremely important when you’re starting a, a, a firm or even a startup for that matter. And it actually came to pass that, that has been a very, very important part of, of my career path as well.

[00:03:59] Barry Ritholtz: So, so it’s certainly a useful set of skills. Yeah. But I’m gonna assume the first business didn’t fail because of bad accounting. Yeah. It’s just a hyper competitive market That’s right. With razor thin margins and as stuff as economies of scale came out. That’s right. The market just dies for that.

[00:04:19] Jeff Chang: Yeah. And that really informed me is that you have to have an edge. I I, I think over the 13 years of founding this company, I noticed that there were actually key features that I noticed even going through Y Combinator, my classmates and people that built very successful companies, they had very common characteristics for their success. Right. In fact, I, I had Asian parents, they optimized for intelligence. Right. Which was very, you know, you get straight A’s you play the violin or the piano and you kind of go through that

[00:04:50] Barry Ritholtz: Process. They’re optimizing for Ivy League admission Exactly. Is what you’re, you’re implying.

[00:04:54] Jeff Chang: Exactly. Exactly. And or be a doctor for

[00:04:58] Barry Ritholtz: That matter. Right. This is so different from Jewish parents. Yeah,

[00:05:01] Jeff Chang: Exactly. So it was, and then as kind of over the years, I realized that the optimization, like if, you know, when I have kids, ’cause you know, I, I don’t have kids, at least none that I know of. But if I did, I would optimize for, actually number one is grit like that. And that grit is the not giving up. Like, like, you know, your company fails, what’s the next thing? Like, you, you know, you pick up yourself from your bootstraps and you, you, you get up and go. It’s almost like the thing is, like, as an example, my parents didn’t let me play video games. Right. But I realized video games actually, if, if you introduce grit, like, you know, if you play Call of Duty, like I was the guy that when I play Call of Duty in my twenties, I would buy the, the headphones that would let me hear whether or not someone’s behind me. ’cause whatever it takes to win, like that type of, you, you ever see that kid that does not wanna lose that like fails, but then gets up and figures out a way to win that is grit. And I feel

[00:05:57] Barry Ritholtz: Like that resilience is more important Exactly right. Than anything

[00:06:00] Jeff Chang: Else. And then the second is, I realize that nothing in this world can be done alone. That success requires you to have partnerships, friendships, and know people that can help build great things. Great things don’t come by yourself. And that’s what I think second is influence your ability to let people see your dream and believe in your dream. Think about this, like, if you’re starting a company, not just selling your product requires influence. Like convincing your first investors, your first employees to quit their jobs, their high paying jobs to make almost nothing and take equity. That’s talk about like selling a dream that’s influence. Like think about, you know, some of the greatest entrepreneurs out there. They, you know, you probably heard like Steve Jobs as a reality distortion field. You know what that is? That’s influence. Right? That is one of the key things.

I think when, when you’re looking at business influence is such a, a, a key thing of, of something that required to have success. ’cause like I said, nothing in the world is done alone. This third, which comes back to my point is creativity. The ability to spot things that other people don’t see. Right. To basically be, to see opportunity, to see things, to combine things together and have that opportunity. Then the last, if you combine it is intelligence. If you do all four, and I can give you examples of people who are immensely successful just with grit. Hmm. And by the way, it’s in that order. Influence, grit, influence, creativity. And last is intelligence.

[00:07:32] Barry Ritholtz: So, so I wanna, I wanna stop you there for a sec. Yeah. Because I wanna spend time going over Y Combinator. Yeah. I wanna talk about this. But before we get there, I mentioned the Naval Academy of such an unusual background. Talk a little bit about what your experiences were like at places like Freddie Mac, the World Bank, FBR and ProShares. That’s such a diverse Yeah. Set of experiences. What did you take away from that life experience and and how did that ultimately lead you to launching your own firm?

[00:08:06] Jeff Chang: Yeah. So I could tell you one of the best things about what the military teaches you is not just teamwork and looking after the people next to you and really making a commitment. But there’s also another thing is work ethic. Like, I, I could tell you that I’m a morning person. I, I didn’t grow up a morning person, but it’s like 5:00 AM I’m up. And, and the funny thing is, my girlfriend’s a night person. She’s like, how are you? Like, sprightly at five 30. And I was like, that is actually learned behavior. Right? So that was like kind of the first thing of, of learning grit and, and you know, tackling the day early on, making your bed things. Those small things in life, I think have been really, I’d say important and, and you know, kind of keystone in in that process. The second is actually when I first started my first job at the World Bank, after trying to start my company, I had to translate fi energy companies in China.

And I had two problems. Number one was I didn’t, my Chinese wasn’t good enough. And secondly, my accounting wasn’t good enough, hence the CPA Right. Came in. I was like, at least I gotta learn one. And then I cut over to Freddie Mac. And if you remember during the 2002, 2003 timeframe is when Freddie Mac went into Restatement. So as a certified public accountant, I was extremely sought after at that time. So I worked at Freddie Mac and I realized that I really wanted to, I read Liar’s Poker by Michael Lewis, and I realized that I, hey, I really wanted to trade mortgages. So I started to

[00:09:42] Barry Ritholtz: Take, which by the way, he said he’s horrified. ’cause he thought this was a cautionary tale. Yeah. And all it did was encourage more people to do that Wall

[00:09:51] Jeff Chang: Street. Yeah, totally. Totally. Reading that book really made me want to be, you know, what he said in the book, big Swinging. Right? Like everybody, it was just a such a, a fun story. It it, it almost painted Wall Street in a specific way, but it was just the interesting part. And, and by the way, it also got me into reading f Bozi about fixed income, about the mortgage market. And, and then I wanted to be a trader. So, you know, I studied for the CFA exam, I got my CFA charter. I didn’t know that would lead me to over a decade of teaching CFA. Right. But that was really fun to do that and, and kind of give back. But, so trading mortgages, Freddie, and then FPRI got to trade during 2008, I got to have a front row seat to seeing the, you know, bear Stearns Lehman, you know, I remember trading repo during the oh eight, September oh eight.

It’s the, the month I lost all my chest hair in, in, in one month. But it was fascinating. I mean, that’s what I thought finance was like. So then, you know, later on I cut over to convertible bonds and options. Then the flash crash hit in, in 2010, which was, by the way, I, I’d never seen an entire trading desk stand up within one minute of everybody’s like, what’s going on? So yeah, I got to see a lot of, of Wall Street in, in my twenties and thirties. It was, it was a definitely a formative time of understanding, you know, kind of what, what made capital markets tick and, and, and understanding and also understanding the pitfalls, the, the hubris of finance that, you know,

[00:11:32] Barry Ritholtz: Well that has to be the big takeaway from oh 8, 0 9 Yeah. Is that markets go up and down. Yeah. And if you’re leveraged Exactly. It’s a problem. And if you’re highly leveraged Yeah. It’s usually pretty fatal. Yeah,

[00:11:47] Jeff Chang: Exactly. And you know, and disasters are always clear in hindsight. Right. And you, you look back and you’re looking at 20, 30% default rates. You’re like, why That would’ve, that would’ve been so clear in your mind when you started to look at some of the data. And so that was really formative. And the other component is, is kind of like what Warren Buffet says. You always know who’s not wearing pants when the water goes out. Yeah. When

[00:12:11] Barry Ritholtz: The tide goes out.

[00:12:12] Jeff Chang: For sure. Yeah. Exactly. And so I always, I I’d say think about, hey, if the tide goes out, make sure the, the money we manage for our clients that we’re, we got pants on. Right.

[00:12:24] Barry Ritholtz: Ri risk management turns out to be more than just a exactly. Phrase. It’s really important if you’re running other people’s

[00:12:30] Jeff Chang: Minds. Exactly. And it’s something that you live and breathe. And what I actually, you know, a lot of our investment products is to try to get our clients to, to understand that. And you utilize kind of, a lot of the tools that we build are basically pants. Like, you know, when the water goes out, make sure that, that you have something there because of uncertainty.

[00:12:51] Barry Ritholtz: That’s to say the very least. So, so let’s talk a little bit about that. You come out of this experience on a desk through the financial crisis. You launch Vest in 2012. What was the motivator? What led you to say, Hey, I think we could do this better?

[00:13:07] Jeff Chang: Yeah, so I had a very short stint at ProShares where I met my co-founder, Koran, he worked on the structuring desk at, at Barclays. And we talked about, you know, like, Hey, let’s start our own firm. And then our first idea was going to be, you know, buffers like, like, like downside protection that we saw in the structure note market. And by the way, this actually segued into the mortgage crisis because in 2008, the largest issuer structure notes was Lehman Brothers. Right. Like, you have a hundred percent protected note and then now you’re standing in bankruptcy court. So that was a big change in the industry. I think the structure note industry went from 120 billion to 30 billion in, in that timeframe from after the 2008 crisis. So I,

[00:13:56] Barry Ritholtz: I’ll tell you a funny story. Yeah. I was a market strategist at a brokerage firm in oh 2, 0 3, and we got pitched a downside protected SMA and I was just sitting in, in a conference room hearing this pitch, what are the, any questions? And I didn’t ask the obvious question that I thought, which was, well, great, the NASDAQ’s down 81%. Yeah. Where were you five years ago? Who needs this now? But the question I asked and got got called into the corporate council’s office for was, Hey, what about counterparty risk? How do we know Yeah. That you guys are gonna be there to, to make the trade good. Sir Lehman Brothers has been here for 189 years. It’ll be here long after you’re gone. I’m like, okay. No, it’s an actual risk that no one was even discussing. Yeah. It was just assumed. So it turned out that, you know, counterparty risk is a real, is a real thing. Oh, it

[00:14:57] Jeff Chang: It, yeah. It’s a very real thing.

[00:14:59] Barry Ritholtz: So we’re gonna talk a little more about Vest and Buffer funds in a moment, but I just wanna get the timing right and talk a little bit about your experiences at Y Combinator. You launched Vest with your co-founder in 2012. You joined Y Combinator in 2015. What, what led you to saying, Hey, let’s, let’s see if we can hook up with the guys over at Y Combinator?

[00:15:23] Jeff Chang: Yeah, so that’s the thing. In finances, there’s not too much innovation, right? Because it’s a lot of regulation and so on and so forth. And so even at our company, we, we always, even our identity today is still, you know, Silicon Valley meets Wall Street. Right. I always think that, like in my mind, if, you know, someone in Silicon Valley were to come into our business, they could end up in jail. Right. Or if Wall Street ends up in, in Silicon Valley, you know, you, you, you might be, you know, just end up in a ditch. ’cause you know, you’ll

[00:15:57] Barry Ritholtz: Be run over for sure.

[00:15:58] Jeff Chang: Yeah, exactly. Because the end of the day is, you know, we went four years with no income. Wow. Right? Like lived off our Wall Street bonuses, me and my co-founder Kran Sue, like, we didn’t get paid for, you know, four plus years to found this company. Like that’s how much you have to the grit and the belief in something. And, and that culture really, really, I think comes out of kind of startup, kind of the Silicon Valley area. Y Combinator at the time

[00:16:26] Barry Ritholtz: Run run by Paul Graham, is it

[00:16:29] Jeff Chang: Paul Graham at, that was the first year Paul Graham stepped down and Sam Altman when I showed

[00:16:35] Barry Ritholtz: Up Ah, gotcha.

[00:16:36] Jeff Chang: Was president of Y Combinator. So 2015,

[00:16:38] Barry Ritholtz: I didn’t realize

[00:16:39] Jeff Chang: 2015. Yeah. Sam was president of Y Combinator. For the folks out there that don’t know. So yc, you know, similar to like a college application, you, you fill out an online college application, you actually don’t need a company. They, they help you form the firm. And you know, the companies that have come out of that program, you know, Airbnb, Reddit, Coinbase, DoorDash, OpenAI was funded by YC Research. So all of that, all of those firms came out of yc. So in fact, I think I read a book called The launchpad, which talks about yc, the companies that they’re, I mean, the first class of YC included Sam Altman, Justin Kahn, who founded Twitch, and Alexis Hanon who founded Reddit. And I think there was like, correct mem May, maybe nine companies. I mean, that’s a all star cast if you ask me for Yeah,

[00:17:33] Barry Ritholtz: Absolutely.

[00:17:34] Jeff Chang: For a class. And so it was definitely someplace that we wanted to be around. There weren’t a lot of finance firms. In fact, vest is the largest asset manager to merge outta yc. So it was definitely something to try something different and really in, get into the Silicon Valley and really push the innovation within, within finance.

[00:17:58] Barry Ritholtz: I don’t know if this is still the case, but a couple of years ago, the standard deal was something like half a million dollars for 7% of the company, plus a three month program of building, iterating, pitching, et cetera. That’s right. Does that more or less sound right? That’s

[00:18:13] Jeff Chang: Right. That’s the deal Today Our deal was probably close to one fifth of that.

[00:18:17] Barry Ritholtz: Oh really? Yeah. Well, 10 years ago. Yeah, exactly.

[00:18:20] Jeff Chang: A lot of changed over the last

[00:18:21] Barry Ritholtz: Decade.

[00:18:22] Jeff Chang: And, and, and they have done a great job. I I, I think they have maintained their, I I, I think the stat was since 2012, 20% of the super unicorns were funded by Y Combinator. Wow. That’s amazing. And then like second place is like 3% and plus or something like that. And

[00:18:43] Barry Ritholtz: This is like a full on bootcamp where it’s three months and they are really taking you through the process. Here’s how you build a startup. Here’s how you iterate. When you first joined yc, did you have any idea what the final product of Vest was gonna be? Or did that experience clarify where you wanted to go? There

[00:19:04] Jeff Chang: Were certain, we went in with the idea of buffers and downside protection. There were certain pivots as far as like, Hey, what’s the best delivery vehicle to start with?

[00:19:15] Barry Ritholtz: Meaning an ETF as opposed to an SA

[00:19:18] Jeff Chang: Versus, exactly. Exactly. But that was the foundational, if you even look at our application, our pitch, it was exactly talking about the need for downside protection, the need to, you know, fix liquidity and credit risk and other types of instruments. Those were kind of the foundational problems because YC always says that like, make something that people want. And then don’t just come up with the ideas. Start with the problem

[00:19:42] Barry Ritholtz: You’re solving for, solving a

[00:19:44] Jeff Chang: Specific problem you’re solving. And the problem needs to be painful enough. And so anybody out there that’s ever thinking about starting a startup, always start with the problem first and make sure the problem is painful enough for your customer. That that becomes, you know, how you solve it can change a little bit. But the problem always existed and, and we thought that that was a, a, a noble problem to, and, and a painful enough problem to, to seek.

[00:20:10] Barry Ritholtz: That’s a very customer focused approach to building a business. I don’t, I don’t know if Wall Street necessarily thinks in those terms. There tends to be an attitude of this is how it’s been, it’s been successful. Why do you think you’re smarter than everybody else? Smarter than the market? Like, that’s the sort of pushback you’ve gotten and that you tend to get when you roll out a different approach. That’s right. How has the experience been marrying the Wall Street ethos where failure is abhorrent? Yeah. And the Silicon Valley mindset, which is, hey, failure just gets you to the solution. It’s just one more step. Yeah.

[00:20:53] Jeff Chang: And, and that’s where kind of the ethos of our Silicon Valley meets Wall Street is that we live in both worlds. Like our background, me and Qurans are Wall Street backgrounds. That, that there is no move fast and break things mentality on our Wall Street ethos. Right. Right. It is measure four times cut once. This is people’s livelihoods, their, their wealth. So that part we did not adopt, not like break things type mentality. That is not, it’s

[00:21:25] Barry Ritholtz: Hard to do that when you’re a highly regulated industry.

[00:21:27] Jeff Chang: Exactly. Exactly. Second is that we also realized you can’t do this alone. It’s not like we’re starting an Airbnb where we can just kind of do X, Y, and Z. We needed partnerships. We needed, like coming back to the point of influence. Like we needed people that really could help us with innovation. Hence we actually only have two investors. One is Siebel Global Markets, Chicago Board Option Exchange, the largest option exchange in the world. And First Trust one of the largest ETF providers here in the United States that has been intricate in the ability to shape and mold the industry. Just like even with the exchange, like, wait,

[00:22:03] Barry Ritholtz: Let me roll you back. Yeah. You said you only had two investors

[00:22:07] Jeff Chang: Now today.

[00:22:07] Barry Ritholtz: Now, today all So let, before we get there, let’s, let’s talk about the, the Post Y Combinator experience. So they give you barely six figures Yeah. For a small chunk of the company. They, they take you through a, a bootcamp Yeah. That teaches you all these different things from focus on problem solving to iteration to pitching investors. Yeah. Who were the early investors? Invest.

[00:22:34] Jeff Chang: So we had our lead coming outta y Combinator was First Round Capital. People aren’t familiar. That’s the company

[00:22:41] Barry Ritholtz: That It’s a great name. Yeah. If you’re doing venture investing.

[00:22:43] Jeff Chang: Exactly. They were one of the first investors in a small company called Uber. And they had, so that worked out okay. Yeah. They got a lot of big wins there. And after that, you know, we had kind of a party round of a lot of different like angels and other, other smaller VCs. But after that, that’s when SIBO came in and, and wanted a, a bigger stake in the firm. But the whole YC experience was very much like the show Silicon Valley. Right.

[00:23:13] Barry Ritholtz: Which I, which I just loved. Yeah. So great.

[00:23:16] Jeff Chang: And to the point where, like, when we got to yc, we rented a hacker house. By the way, the house that we rented was called Hacker House. And it was a one story building with like three bedrooms, not enough bedrooms for all of us that were working there. I think Koran had to sleep on the floor on a mattress for three months. And by the way, this is coming from being over a decade on Wall Street. Like, we’re now sleeping on the floor.

[00:23:44] Barry Ritholtz: Hey, there’s nothing to do, but get this done.

[00:23:46] Jeff Chang: EE exactly. And this is why I I say like, sometimes like if a former trader on Wall Street ends up in Silicon Valley, they may end up in a dish. ’cause like you have to go four years, no pay sleep on the floor. It’s not fun. Where you’re used to like wearing, you know, suits and loafers on Park Avenue. It’s a big shock to the system. But that’s the thing is like, you know, at the same time, it’s, it’s to okay, sleeping on the floor, it’s better than sleeping on the ground when, when you’re in the military, but that, that’s the grit that you kind of go through. Right.

[00:24:14] Barry Ritholtz: Coming up, we continue our conversation with Jeff Chang, co-founder and president of Vest, talking about his experiences at Y Combinator. I’m Barry Riol. You are listening to Masters of Business on Bloomberg Radio. I’m Barry Ritholtz. You are listening to Masters in Business on Bloomberg Radio. My extra special guest this week is Jeff Chang. He is the co-founder and president of Vest. The firm manages $50 billion in ETFs that are described as outcome oriented investing. Some people call them buffer funds. So you have this experience with Y Combinator, any of that graduating class with you, you’re still in touch with who else were Oh,

[00:25:11] Jeff Chang: Yeah. So I’m not sure if folks out there know GitLab. Oh, of course. Sid. Sid was our, our group. My group,

[00:25:18] Barry Ritholtz: No relationship to GitHub, which predates that by

[00:25:22] Jeff Chang: A long time. But yeah. But GitLab was our, I think they IPO’ed on the Nasdaq, I think over 5 billion or something like that. They’re doing really well. There was, the equipment share was also our, our batch. A lot, lot of lot of big winners in in our, and by the way, you’ve probably been to college where you go into a lecture hall Right. And you have your first day of class. The first day of yc. You know what they tell you? They’re like, you know, 4% of you guys in this room will be billionaires. Right. You know,

[00:25:54] Barry Ritholtz: No intimidation factor at all,

[00:25:55] Jeff Chang: By the way, that’s the math. Right? Right. Sure. Like on average it’s a 4%. I I think right now it’s like five to 6% unicorn rate. But how many classes can you go through that? Like, you’re like, Hey, 4% of four to 5% of you guys are gonna have extremely successful companies coming outta this class. And by the way, you look around and you’re like, oh man, is that really possible? And then you, you, you blink 13 years later, you’re like, wow, it really did happen. Like, there, there’s incredibly successful firms and incredibly successful people. And you look back and like, even now, I look at my group partners. I, I look back, my group partners were incredible. I had Gary Tan who found an initial eyes and also is now the president, COY Combinator, Alexis o’ Handon, founder Reddit. Justin Conn founded Twitch Cap Meac, who was like an allstar in, in in marketing and pr like I had an Allstar group.

[00:26:47] Barry Ritholtz: Yeah, no, it definitely, definitely sounds like it. We’re talking about winners, but Silicon Valley wears losers like a badge of pride. Yeah. Like it’s, hey, this is what’s expected, which is very different than the way the East Coast tends to approach things. Tell us about that. Not being afraid to fail, not being afraid to try things, iterate and take this doesn’t work. Let’s go with that. How, how different is that experience on the West coast than what you experienced on Wall Street?

[00:27:22] Jeff Chang: Yeah, I, I mean definitely in Silicon Valley, failure is, is okay. They, they have a saying if you’re gonna fail, fail fast. Right. Whereas I feel like on Wall Street is like, you don’t want to fail fast. Like that’s called a blow up. Right. Right. So there, there’s some parts. Given the industry that we’re in, we had to ignore some of the, the, the aspects of it. I think everything that we did, I wouldn’t say was ultimate failure. Maybe not the success that we wanted because we wanted to make sure everything we built were strong in foundation. Right. It would like last stand the test of time no matter what happened. Hmm. Maybe not wildly successful, but then that, that’s how you pivot. So it’s not necessarily failure per se, but not the success you’re looking for. Then pivot and try to find other ways to deliver and how to solve the problem better. But I, I still think that the idea of, of not being afraid of failure and that grit and the ability to, you know, pick yourself up. It, it’s that attitude that like, you know, this is not the end. Failure is just the, the mother of success. And you just have to keep learning from those mistakes. Is everything is a learning process. I can’t tell you one person that I know that’s successful. That has not failed.

[00:28:40] Barry Ritholtz: No, that makes perfect sense. You know, you, you don’t know what’s gonna work and you don’t know what’s not gonna work until you try. Yeah. And if you know there, the, there’s a story about, hey, if you’re not failing occasionally, then you’re just not taking enough risk. Yeah. Say to say the very least. All right. So, so let’s talk a little bit about how this developed. You come out of Y Combinator sometime in 2015. When did you first start taking client assets, client money?

[00:29:12] Jeff Chang: Well, NYC we were taking client assets. I think we launched our first mutual fund in 2016. It was the first buffer fund of, of its kind. And then,

[00:29:24] Barry Ritholtz: So wait, let’s stay with mutual funds, which have their own complications with capital gains tax. Sure. Given what you do primarily with derivatives and options in order to create that buffer, how, how does that play out in a mutual fund wrapper?

[00:29:41] Jeff Chang: Yeah. There are obviously challenges that may not be as, let’s say, the same as like an ETF, that, you know, in 2019 they introduced the in kind. This is also another example of the partnership with sibo. It’s, it’s been

[00:29:57] Barry Ritholtz: Around for real estate for forever it seems. Yeah, that’s right. And it just took Wall Street a while to catch up to that. Explain what in con in kind creation and redemption looks like. Yes. And what it means to you.

[00:30:09] Jeff Chang: So in mutual funds, there’s a challenge in, in some cases that in, if there’s a redemption, you would sell your securities, which could have the potential to realize gains. And ETFs not just unique to these ETFs are all ETFs. They have the ability to, let’s say in kind securities. So when someone wants their money back, instead of giving them market maker selling securities and giving them cash, in some cases you can give them securities thereby not potentially realizing the gain for, for the shareholders. So it per has the potential for tax efficiency by having in kind. Now, prior to 2019 October of 2019, that was not, we weren’t able to do that with options that was introduced in October of 2019. So we launched our first Buffer ETFs in November of 2019 in partnership with our partners at First Trust. And so that has been one of the fastest growing areas, not just for our firm, but as the ETF industry as a whole.

[00:31:15] Barry Ritholtz: So, so let’s talk a little bit about what a Buffer fund does. What are the advantages? What are you giving up in order to obtain those vantages? What, what’s the largest fund? What’s the largest ETF now at Vest?

[00:31:30] Jeff Chang: So the largest buffer fund and the one at Vest is BUFR. And it’s built good ticker. Yeah. It’s built on the foundation that, you know, the, the kind of fundamentals of the strategy is the buffer strategy, which is, you know, let’s say you get s and p exposure for one year, the first 10% is protected. So as an example of strategy, if s and P is down 10, you’re flat for the year and then you get upside up to, let’s say a predetermined cap. So let’s say s and P is up 15, you’re up 15. But the most you can make is 15. So if s and P is up 16, you’re up 15. Right. So you’re capped out at that 15%

[00:32:09] Barry Ritholtz: Percent so’s like 23 and 24 kind of unusual. Sure. You don’t usually see 25% two years in a row. Yeah. But if you were in the fund in 22, down 22% Yeah. Means you’re only down 12%. Is that That’s right.

[00:32:26] Jeff Chang: That’s right. So

[00:32:27] Barry Ritholtz: That’s the trade

[00:32:27] Jeff Chang: Off. Yeah. And the, and here’s the thing is that most people don’t realize these strategies have the potential to outperform the market. Even if you’re talking about, you know, high double digit equity returns. ’cause think about this, in 2022 because of inflation, when interest rates went up, stocks and bonds both went down at the same time. Right? Right. You could have mixed your stocks and bonds any way you wanted in 2022 you were

[00:32:48] Barry Ritholtz: Down 60 40 was negative. Exactly. In 2022.

[00:32:51] Jeff Chang: And unless you were managing money 40 years ago, you had not experienced inflation. Right. And you couldn’t hide anywhere. I mean, you were like Tom Brady choosing between alimony and child support while taking your kids to juujitsu practice. Right. Like the thing is there was nowhere to hide. Right. Right. Whereas if you were hedging, and the great thing about hedging is if you buy s and p and you buy an s and p put that put is perfectly negatively correlated to estimate. It’s like buying

[00:33:17] Barry Ritholtz: Insurance. It’s an inverse. Exactly. Its the

[00:33:19] Jeff Chang: Opposite. Right. And so imagine if you had a strategy that did not participate in the majority of the drawdowns in 2022, that means you had more to invest to take advantage of the gains in 20 23, 20 24, and 2025. This is the compounding effect of winning without losing. Right. It’s the compounding effect of playing offense and defense at the same time. Because the end of the day is, a lot of times, you know, these types of strategies are not the get rich game. If you’re 20 years old, probably not the strategy for you. But, you know, in in, in our industry, a lot of the people that have wealth, they’re in the stay rich game. Right. These types of strategies are in the stay rich game. ’cause if, if you have wealth, you just don’t want to be poor. Right. So that’s why that’s the kind of crux of protecting your, your equity exposure.

And the, the idea is, the issue with hedging has always been that to hedge with options and so on and so forth. One of the biggest, and they had surveys on why, you know, investors and financial advisors don’t hedge with options. And they all, everybody said the same. Two things, compliance and scalability. You know, the compliance burden associated with trading options and the scalability. ’cause when you buy a fund, you buy a stock, you, you could put in your portfolio, fall asleep for 30 years, maybe you boun, rebalance once a quarter. You buy an option every 30 days, 60 days from now, you have to trade it by having it inside a fund, we can trade that for you. And so now you can asset, allocate, rebalance once a quarter. It solves a lot of those issues. And, and this is the, the thing that I find very interesting is two things.

Number one is these strategies have been around for over 30 years. The buffer structure note has been around for years. Buffer annuities I think were introduced in 2010. All we did was cut the bank insurance company out. Like instead of having the banker insurance company hedge themselves with options and then issue you a policy or issue you a No, we just said, why not just put the hedge in a fund and now you own it? We cut the middleman out of the middle. The other component is to think about in business that I, I always look back, so Richard Thaer, the professor at University of Chicago won the Nobel Prize for behavioral finance. Right. The

[00:35:31] Barry Ritholtz: Nudge essentially created the field.

[00:35:32] Jeff Chang: Yeah. The nudge. And I believe one of the studies by, by Cornell University had this study of, I think they had kids in the lunch line. They gave them free apples. Like you get the end of the, you get a free apple. Right. By the way, the consumption was like less than like, I don’t know, 20%. Like it was a very low consumption rate. No one took the apple, then they cut the apples up and they put them in little bags. By the way, the consumption went through the roof. Why? This was the nudge, this was the idea that you make it simple, people will use it. Think about options as apples. And then that we had bagged those apples to make it easier for the user to consume them without the compliance and scalability burden to them. Because theoretically, any broker or any financial advisor out there can actually trade those themselves. But that’s like the same thing. Like every child could sit there and cut their own slice their own apples, but they don’t wanna do that.

[00:36:27] Barry Ritholtz: So let me ask you, ’cause ’cause you’ve brought this up a few times, and I wanna hone in on this. Is your target consumer mom and pop main street investors? Or are you focused more on the advisor channel or brokerage channel? Who, or, or all three, some combination.

[00:36:46] Jeff Chang: We are not that focused in the retail space mostly. And, and by the way, I would say a hundred percent of our focus is in financial professionals. Really. Because that, those are our partners. Those are our, the, the people that we stand side by side with. We build products that, those are the people we’re solving problems for them, which they’re solving problems for their clients. We stand side by side with the financial professionals that manage, you know, the,

[00:37:19] Barry Ritholtz: And once you bring them up to speed, it’s, it’s incumbent on them to find the clients that think are the right fit for this. And they get to explain that rather,

[00:37:28] Jeff Chang: Rather than Exactly, because every single client is different and unique. We make products across and every client is different. And how that, that gets utilized. We, we help the financial advisor even, you know, how to best build and achieve their client’s investment objectives. But as far as like the end client, that, that’s typically not, not our customer.

[00:37:49] Barry Ritholtz: So, so I mentioned 60 40 earlier, does a buffered fund act as a substitute for 60 40? In other words, if you own, whether it’s 60 40, 70 30, you own bonds for income, of which there hasn’t been a lot over the past 15, 20 years, but also as a non-correlated asset with equity other than 81 and and 2022 does this and it offsets the volatility in drawdowns inequities. Do buffered funds behave similarly to a 60 40? Is that the thinking? I

[00:38:25] Jeff Chang: Wouldn’t say similarly. Let let me give you a, a kind of a how, how we think about it. So if you look at, let’s say, a strategy of a 10% buffer on s and p, in fact, you know, there are indexes out there that track these. Even if you compare that to let’s say like a BlackRock 60 40 portfolio, you actually notice that the standard deviation is almost identical. The volatility is very similar Right. Over the long term. But the source of the risk management is different. Right. You’re actually hedging, you’re not hoping that the correlation between stocks and bonds, the negative correlation is there that, you know, when my stocks go down, I hope my bonds go up kind of situation. Right? Well

[00:39:06] Barry Ritholtz: Historically they do most of the time. Yeah. They didn’t in 2022. They didn’t in 1981. Exactly. You know, so it, it’s every 40 years or so we seem to get this headache

[00:39:16] Jeff Chang: Or with inflation at, you know, 3%. What happens if inflation rears its head again in 20 year,

[00:39:23] Barry Ritholtz: The next rising. Exactly. You’ll end up with the same issue the next time we see a serious set. Exactly.

[00:39:29] Jeff Chang: And this is why we say why not diversify your risk management and hedge. So if I have a hundred dollars portfolio, and let’s say I have $60 in equity, $40 in fixed income, and let’s just say I take 10 bucks out, I put six, take six from equity, four from fixed income. I put it into let’s say a 10% buffer strategy. In s and p, perhaps the standard deviation of the portfolio could be very, very similar. But notice the source of your risk management has changed. You’ve introduced hedging as the source of your risk management without the compliance, without the trading. Scalability, issues of options. You’ve introduced hedging as the source of risk management if inflation were to rear its head. ’cause the thing is, this is what everybody needs to ask themselves if inflation were to come back. Right. Which is a very, is not a, is a very, there’s a high

[00:40:20] Barry Ritholtz: So non-zero

[00:40:21] Jeff Chang: Possibility. It’s

[00:40:22] Barry Ritholtz: No possibility way above that. Yeah, exactly.

[00:40:24] Jeff Chang: What in your portfolio is going to save you if 2022 repeats itself? That’s the question everybody needs to ask. I always get the, I answer commodities, great commodities. It’s a timing trade, right? That’s right. You can get in, it’ll work. But when it’s not inflationary, what happens to that trade? I, I mean I’m not, well

[00:40:44] Barry Ritholtz: Lemme point out that gold didn’t do great in 21 or 22. Yeah. It’s only in the past few years where it’s really exploded higher.

[00:40:53] Jeff Chang: That’s right. That’s right. So I’m not smart enough to time that trade. And that’s the great thing about these types of solutions is you don’t have to time the trade, right? Like you’re diversifying your risk management through just hedging. And like I said, repeat it again. This is the stay rich game, right? How do we protect wealth? Not, not like make exorbitant amounts of it, but protect wealth and, and, and get a, a decent return from, from people’s wealth.

[00:41:22] Barry Ritholtz: So buffer is 10% hedged on the s and p 500. Tell us about some of the other ETFs you guys run.

[00:41:29] Jeff Chang: So one of the kind of overall themes that we’ve seen in the market is, you know, two things that really people are looking for is downside protection. But the other one is income generation. As the boomers are in retirement, the need for yield has really shown how high it is. I mean, if you look at the derivative income space, I think in 2018, and Morningstar ranked 58th last year is ranked ninth in flows. Right? People are looking for income. And as volatility goes up, just like strategies, like writing cover calls are extremely, it’s a another way to derive yield by monetizing volatility in different asset classes. You could do it in gold, you can do it in Bitcoin, you can do it in equities, you can do it in fixed income. And that’s the thing is people were always thinking one dimensionally that like the innovation is always about thinking three dimensionally when everybody else is thinking in two dimension. Right? This is why we have, you know, build strategies to derive income from, you know, not just equities, but fixed income. But for from gold, from bitcoin, from any asset class you can. So

[00:42:37] Barry Ritholtz: Give us a few ETFs that are primarily income focused. Yeah.

[00:42:41] Jeff Chang: So one of our biggest ones is K and G, which tracks the dividend aristocrats our DVI, which tracks the dividend achievers. These all provide, you know, attractive level of yield I think. So

[00:42:57] Barry Ritholtz: Dividend aristocrats tend to be high dividend, low price. They tend not to be high PE companies. Yeah. So they’re fairly stable. Is that, is that, yeah.

[00:43:08] Jeff Chang: So the companies that have grown their dividend, this was created by s and p back in 2005, companies that grown their dividend for 25 consecutive years. Wow. And these are dividend growers. They’re not dividend payers. So they typically, I believe, you know, yield less than 2%, but they’ve grown their dividend for 25 consecutive years. So for a company to grow their dividend for 25 consecutive years,

[00:43:29] Barry Ritholtz: That’s a stable business. Yes.

[00:43:31] Jeff Chang: And it has to cash flow. It’s not a pe play. Right, right. For, for all intents and purposes, it, it is companies that have to have strong moats. And the other thing that people miss is good corporate governance. ’cause who makes dividend policy? The board for a board to never cut a dividend for 25 years. It, it actually was a filter for good corporate governance. Now

[00:43:52] Barry Ritholtz: And that stock symbol is that ETF symbol is

[00:43:55] Jeff Chang: K-N-G-K-N-G.

[00:43:57] Barry Ritholtz: Yeah. And, and you guys generate additional income on that with cover cover

[00:44:03] Jeff Chang: Call writing. That’s right. That’s

[00:44:04] Barry Ritholtz: Right. So if it’s a 2% yield, what do you actually

[00:44:07] Jeff Chang: Ballpark generating? So we’re, our distribution yield’s probably in the past year over 8%.

[00:44:13] Barry Ritholtz: Really? That’s a big number. And we’re on

[00:44:15] Jeff Chang: Average, I believe covering around 20% of every single name. So, you know, if I have a hundred shares of Walmart, I’m writing an at the money call and let’s say 20 of those shares as an example to achieve that target income. So one of the things that core beliefs that we have when writing cover calls is like one of the biggest drivers is stock selection. You pick good stocks, you get good results. Right. While you know the aristocrats, they don’t have the high flying mag seven names. Right. But definitely as you look forward into the windshield, these are really gonna be the names as the market bronze out. Right? Like I really do think in the next year you’re really looking at kind of a barbell approach where you, you, you have the NVIDIAs and the, and the high hyperscalers in your portfolio, but you really need to have the strong staples that cash flow, especially.

[00:45:05] Barry Ritholtz: What are, what are some of the names in KNG?

[00:45:08] Jeff Chang: Well, you got like Chevron, Walmart, like your really blue chip names that are there. I mean, look at Chevron. They, they, they have the potential to be, you know, one of the beneficiaries of oil in Venezuela, right? Like they were, they were there before. They, these are the cash flowing like crime like companies that like, like I said, grown their dividend for 25 consecutive years. These are strong, strong names that are out there.

[00:45:34] Barry Ritholtz: Do you, do you do anything with fixed income on the yield side? Yeah. As well.

[00:45:37] Jeff Chang: Yeah. So we have cover calls on high yield tracking. HYG gives you also, I believe a double digit distribution yield only covering about, you know, 20 to 25% of the portfolio. So you’re still getting over, you know, on a weekly basis. 70.

[00:45:55] Barry Ritholtz: And and what’s that? ETF symbol

[00:45:57] Jeff Chang: HYTI Heidi. Yeah. And,

[00:46:01] Barry Ritholtz: And what about Commod? Do you do anything on the commodity side? So

[00:46:04] Jeff Chang: We have gold, I-I-G-L-D. So you know, biggest knock on gold has been the hunk of metal. Since your portfolio doesn’t do anything now you can monetize the volatility and have, you know, potentially

[00:46:16] Barry Ritholtz: Same process covered coal writing. Exactly. So it, this is why CBO is a partner with you guys. How does that relationship help you manage all of this option writing all this? That’s a great call

[00:46:30] Jeff Chang: Activity. That’s a great question. So let’s take I Gold as an example, right? Prior to that fund, GLD options stopped trading at four o’clock. By the way, this is one of the reasons why SIBO partnered with us, is how do we solve certain issues in the option market for the construction of of funds, right? If options stop trading at four o’clock and I need to know the close, I can’t create an ETF on that. That’s right. Right. SS and p options. SPI options, they trade, they close at four 15 today. GLD options stop trading at four 15. By the way, that’s a really cool statement to say that the entire street trades GLD options, that extra 15 minutes because we wanted that,

[00:47:15] Barry Ritholtz: That’s great.

[00:47:16] Jeff Chang: But that’s because you

[00:47:17] Barry Ritholtz: Have, you have to take the closing price at four and then use it for an in day

[00:47:21] Jeff Chang: Hedge or Yeah. We that we need that, we need that option market to be open that extra 15 minutes. And by the way, that, that those products by First Trust, invest, are, are the reason why we have an extra 15 minutes to trade GLD options. So if you’re, you’re late and you’re trading at 4 0 5, that, that’s us.

[00:47:38] Barry Ritholtz: And, and option trading is so much more complicated. So much more difficult. Yeah. Like you, I started on an equity desk, but have always been a little bit of a, an option junkie. Yeah. ’cause it’s so fascinating and most people use, don’t use options correctly, they’re just making like a lottery ticket bet. Yeah. Which tends not to be smart. You guys are using options for a very specific purpose to achieve what you describe as a defined outcome. Yeah. Solving

[00:48:09] Jeff Chang: Result, a problem,

[00:48:10] Barry Ritholtz: Solving a problem started with a problem. Really interesting. Yeah. Coming up we continue our conversation with Jeff Chang, co-founder and president of Vest. I’m Barry Ritholtz, your listening to Masters in Business on Bloomberg Radio. I’m Barry Ritholtz, your listening to Masters in Business on Bloomberg Radio. My extra special guest this week is Jeff Chang. He’s president and co-founder of Vest. The firm specializes in outcome oriented investing via primarily ETFs. They run over $50 billion in assets. Yeah. Before I get to my favorite questions, I want to ask any, so we’ve covered stocks, bonds, commodities, you mentioned crypto. What are you doing in terms of crypto and generating additional defined outcome results? Yeah. Using derivatives.

[00:49:15] Jeff Chang: Yeah. So we have a strategy also target income almost, I believe about a 18, 19% yield. And you’re still only covering about 20%. So that strategy tracks Bitcoin. So you can get on a weekly basis, let’s say, you know, 70, 80% of the upside in Bitcoin. And then a, you know, really high, high, almost 20% yield by monetizing the volatility. It’s the same thing because like, just like gold, some of the knock is, is that it just sits in my portfolio doesn’t do anything. And the value,

[00:49:47] Barry Ritholtz: Well no one could say that about Bitcoin. Yeah. It’s always doing something going up or going

[00:49:51] Jeff Chang: Down. Yeah, yeah, exactly. And

[00:49:52] Barry Ritholtz: What’s the ETF symbol for that?

[00:49:54] Jeff Chang: I bit, I’m sorry. I’m sorry. I’m, I’m sorry. Not I That’s black eye. Yeah, yeah. Defi. D-F-D-F-I-I. That’s right.

[00:50:02] Barry Ritholtz: DFII. Yeah. And so that’s options. How much of the upside, how much of the downside do you get and give up? Or is it just geared,

[00:50:13] Jeff Chang: We’re just writing cover calls on to Target, you know, a specific yield. I, like I said, I think anywhere from recovering every week about 20 to 25%. And at the money, how

[00:50:23] Barry Ritholtz: Often do those roll? Every week. Every week. Wow.

[00:50:25] Jeff Chang: Every Friday. Yeah. The reason why we like Weaks is that when you sell a call, you want the premium to go to zero, right? That’s right. And that decay accelerates in that last week if you’re selling a monthly option. So if you like do it four times a a month, you, you, you have the potential to generate more yield because you’re always capturing that extra decay. It’s like, it’s like football tickets, right? Like you ever go on StubHub like game times at one o’clock and you, you, you go on StubHub at 12, the ticket starts to drop like a rock. Right? Imagine if you kept tracking that and you, you made money off that, that that drop Right. And everything kind of follows that, that in fact, there’s actually only one thing that doesn’t follow that, you know what that is?

[00:51:09] Barry Ritholtz: Go on

[00:51:10] Jeff Chang: Giants tickets, they decay before the season starts.

[00:51:14] Barry Ritholtz: Well, as a guy who used to be in New Jersey for sure. Or

[00:51:18] Jeff Chang: Jets tickets, actually both of those are anomaly. They

[00:51:21] Barry Ritholtz: So really, so in other words, bad assets Yeah. Don’t generate good option returns. Yeah. That, that’s pretty reasonable. Yeah. How often do things get called away? That’s obviously the risk when you’re writing calls. Sure. How, how do you manage around that? How frequently is that built into your models? I mean,

[00:51:39] Jeff Chang: That can happen Oh, pretty frequently. But here’s the deal. Like, like think about this. And this is just a concept of of of of, let’s say I collect a $2 premium and the stock goes up $1.

[00:51:53] Barry Ritholtz: You’re good. Yeah.

[00:51:55] Jeff Chang: I made a a dollar, but it still got called away, but I still made a dollar. I just buy the stock back or however, however way I deal with the assignment, depending on the, the strategy. So the idea is as long as the stock doesn’t go above the premium, if I’m writing out the money or what, what I’ve actually gotten. Exactly. It

[00:52:10] Barry Ritholtz: Gives you a buffer to repurchase the stock not at a loss.

[00:52:14] Jeff Chang: Exactly. And, and this comes into what we call about the implied versus realized premium meaning options. If I look historically of a particular asset, whether it be a stock or a commodity or whatever, and it, it historically moves X I’m not gonna sell the premium at that number. Right. It’s gotta be X plus, right? Right. Just like when you sell car insurance, like if my expected loss is a thousand dollars, I’m not gonna sell the premium F for a thousand. I’m gonna sell it for $1,200 to make 200. Right. That extra little bit. Right? So in options, they have what’s called the implied versus realized premium. And so that’s really kind of where you’re trying to capture is, is the implied volatility versus what the realized volatility. And you’re hoping that the implied will be greater than the realized. I mean that’s the hope and option, especially when you’re selling them. Right. I think there’s a stat that like, you know, 60% or 70% of the time the person selling the option wins the trade. Right? Right.

[00:53:12] Barry Ritholtz: Most, you know, old option traders don’t die, they just expire worthless. Yeah, exactly. Is the old, old desk joke, but Exactly. You know, if you are a writer of options, you’re making a very specific bet. Yeah. And if you’re a purchase of options, you’re making a very different bedside.

[00:53:25] Jeff Chang: Yeah. Yeah. I mean, you see this, you know, in some cases the buying options is like you said, it, it, it, it, it can, you know, even Warren Buffet said there could be weapons of mass destruction. I mean, you could see these zero day options that people are buying.

[00:53:38] Barry Ritholtz: Yeah. That’s become crazy.

[00:53:39] Jeff Chang: I mean, those are like scratch off lottery tickets. Right, right, right. Who’s buying them? I don’t know. The kid in his mom basement popping his pimples eating manna sandwiches. I don’t know. At,

[00:53:47] Barry Ritholtz: At one point in time I imagine that there were market makers that had a hedge that for reasons Yeah. That were complicated. They were stuck with overnight positions. Yeah. Like I almost understand that, but the day traders playing with these Yeah, this is fanduels and draftking. Yeah. Pure speculative nonsense. Yeah,

[00:54:08] Jeff Chang: Exactly. So that’s why we don’t have anything in that space, but it is something to look at from afar.

[00:54:16] Barry Ritholtz: Huh. Really, really fascinating stuff. Last question before I jump to my favorite questions. So you are constantly thinking about how do we hedge this position? How do we create a buffer? How do we define a specific outcome for clients? What do you think the average investor isn’t thinking about relative to that approach? But, but perhaps should be. What, what do you think most people are kind of missing or not paying enough attention to? And, and it could be a geography, it could be a policy, whatever. But you, you’re obviously thinking about a lot of things differently than the typical index purchaser. What are we missing?

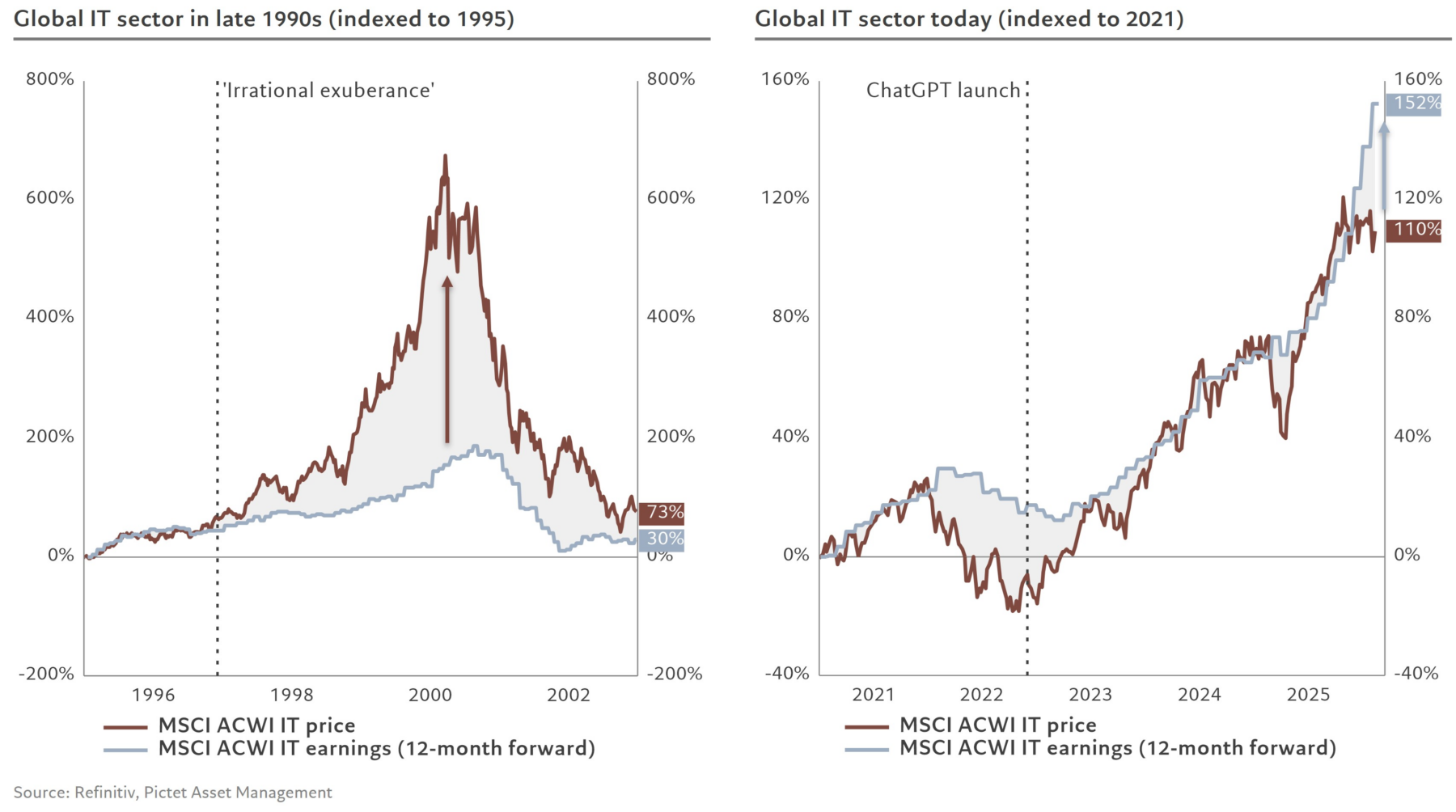

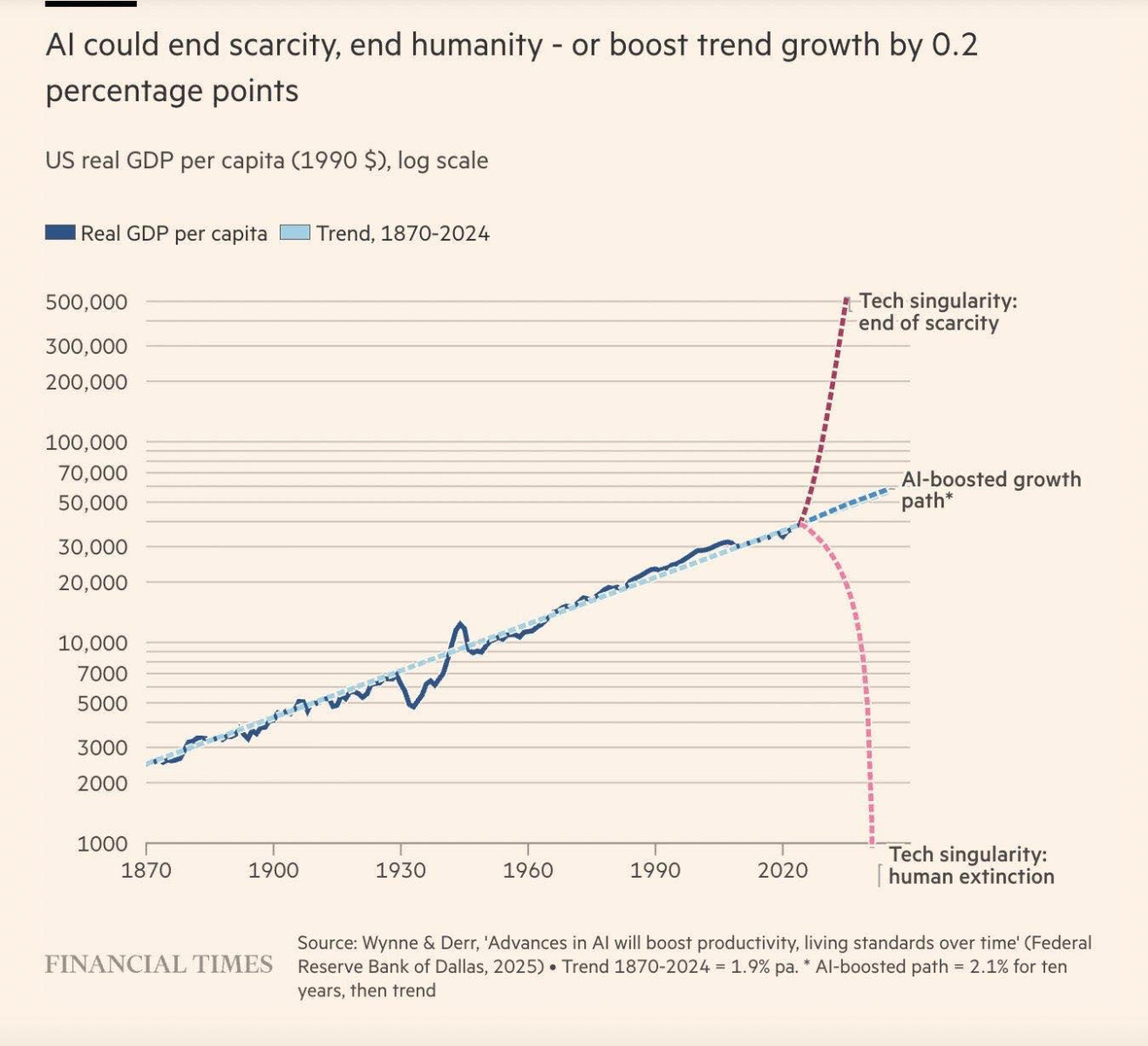

[00:54:59] Jeff Chang: Yeah, I think, you know, while we’ve had a tremendous amount of growth in, in kind of the option space of downside protection and, and the income generation part, I think a lot of the market is still, I think thinking two dimensionally in the stocks and bonds. Right? Like instead of just diversifying across, think about you could still diversify, but think about other ways to shape your return. Right? Or thinking about income generation out of the equity portfolio think about income generation or boosting yield in your fixed income part of it. And then also thinking about risk management beyond diversification there, while there is a lot of good part of the financial professional space that is picking up on this, I still don’t think like we are just tip of the iceberg at this point. Right. Hmm. That’s on one, one standpoint. I think people are, are still missing. The second I think is the, I think one of the biggest drivers in the market today, and no one would disagree is ai. Right? For sure. However, that’s not the part that people are, are, are missing that, you know, having been through the two thousands, I really feel like this is like 1999, 2000. Like think about the stocks that were big then, right? Like you had

[00:56:15] Barry Ritholtz: Juniper Networks. Yeah. Metromedia fiber. Wow. Right.

[00:56:18] Jeff Chang: Like I remember you guys remember price line

[00:56:21] Barry Ritholtz: Global crossing. Yeah. Well pri you know, a lot of these companies have been either absorbed into other companies. Yeah. And still price line Expedia, there’s a through line there. Totally. How is pets.com not Chewy today? Yeah. So some of ’em were just a little early.

[00:56:37] Jeff Chang: Exactly. So now let me ask you, who won that trade? Facebook, Google, Netflix, Amazon. Amazon,

[00:56:42] Barry Ritholtz: Apple, Microsoft. A

[00:56:44] Jeff Chang: Lot of those companies were private or startups then Google,

[00:56:48] Barry Ritholtz: Right?

[00:56:48] Jeff Chang: Yeah. Like, think about that. And I think that’s the same, like history doesn’t repeat itself. It rhymes. I actually think a lot of the, kind of the hugely successful companies from AI are in startup mode. So they’re at y combin error. 90% of the, almost 80 90% of the companies at YC are AI driven. They have, I’ve seen an article recently. Their month over month average for the batch is double digits, meaning their revenue is growing over 10% month, month to month, month over month. Wow. Or, or in some cases week over week,

[00:57:23] Barry Ritholtz: The week that, that’s unbelievable. And I, I said to someone the other day, someone said, who’s gonna de Deron Nvidia? And I said, the founder of that company hasn’t graduated high school yet, but he’s coming or she’s coming. He’s not, it’s not impossible. All right. Let’s, let’s jump to our favorite questions that we ask all of our guests. Starting with, who are your mentors who helped shape your career?

[00:57:49] Jeff Chang: Oh, that’s a great question. I would actually have to say my brother. Really? Yes. And

[00:58:00] Barry Ritholtz: In

[00:58:00] Jeff Chang: What way? My, I have an older brother. He’s four years older than me. He’s the overachiever, I’m the underachiever of the family. Okay. So my brother, I remember growing up, he was like the, he was good at math and science. I would literally show up to class and they’d be like, oh, you’re Bill Chang’s brother. You must be smart by the way, you know what that does to you as like a, a lot of pressure. Yeah. A lot of pressure. So he went on, he worked at Apple and then was at Tesla. I think he was chief architect of the Dojo Dojo project. If, if PE folks that aren’t familiar with Dojo, it’s the AI system at Tesla that coded the self-driving. Hmm. Right. He recently, and in fact, Bloomberg wrote an article about his firm density AI that I think they are one of the, the first companies to really kind of take on. ’cause the Dojo, I think system is one of the, one of the more efficient ways that can take on Nvidia for the chip. So that’s why it’s funny that you said like, Hey, the person that’s gonna deth throw Nvidia, may, may not, may still be in high school. I was like, yeah, he might just be four years older. Older than me. Or Right.

[00:59:13] Barry Ritholtz: Or he could be deep into the process already.

[00:59:16] Jeff Chang: Yeah. Yeah. So they recently, like I said, like Bloomberg just wrote an article about them on density ai. And he, he has been extremely, like, a lot of times people ask like, Hey, did you work that hard? ’cause your parents were, you know, like tiger parents? No, actually I was just chasing my brother the whole time. It was definitely a different dynamic and yeah. I couldn’t be more proud of him. And a lot of times people are like, Hey, what, what tea are the Changs drinking? Because we’re, but we get along great. While we’re competitive, we, we support each other. But he’s been, you’re in

[00:59:54] Barry Ritholtz: Different fields, so the competition. Exactly. Yes,

[00:59:56] Jeff Chang: Exactly. He’s an engineering. I I’m in finance

[00:59:59] Barry Ritholtz: Financial engine. Yeah. Yeah, exactly. So similar, similar background. Exactly. Let, let’s talk about books. What are some of your favorites? What are you reading right now?

[01:00:05] Jeff Chang: Yeah. Well, I said Liar’s Poker was Right. Classic was a very influential one. Classic. Yeah.

[01:00:10] Barry Ritholtz: Just had its 30th anniversary, I think last year. Yeah.

[01:00:12] Jeff Chang: I like, I thought was really good for me it was the book Influenced by Robert Chelani.

[01:00:19] Barry Ritholtz: Fantastic.

[01:00:19] Jeff Chang: It was a great book. The kind of along with that, how to Win Friends and Influence People. I think those are great. I actually in finance, one of my first ones was The Intelligent Investor by Ben Graham. Yeah. Ben Graham. Those are kind of cornerstones. Yeah.

[01:00:34] Barry Ritholtz: That, that’s a great list. Yeah. I know you are on planes a lot. Yeah. When you’re not reading, what, what are you streaming? What’s keeping you entertained on these long cross country flights? Either podcasts or Netflix or whatever.

[01:00:48] Jeff Chang: I do listen to podcasts. A master’s in business. Yeah. However, there’s a new thing that I I I’ve been doing, actually, it’s not a book. Right. And it, it, it’ll probably be hit everybody differently on, on what I’m doing here. Okay. And I could tell you, I got this from a good friend of mine and he’s gonna kill me for saying this. So I’m good. A friend of mine, his name Matt Bellamy, he’s the lead singer in the Muse. Okay. And he, he actually taught me this, so I can’t take credit for this. We go into chat GBT and he actually sent me the prompt and we prompt chat, GBT tell me in the last two weeks what you have learned that is beyond human comprehension. Something along those lines. Really.

[01:01:37] Barry Ritholtz: How

[01:01:38] Jeff Chang: Fascinating. And by the way, it spits out all this stuff because if you think about it, humans, like we as a human, you could get a PhD in biology, you get a PhD in astrophysicists, you get PhD in chemistry. But like, you’re the expert in their field. But think about this, that like chat GBT passed the bar exam in like, I don’t know, like a couple weeks. Right, right. So it’s becoming experts in everything and then it’s combining all of those things together. So how many like PhDs and chemistry astrophysicists do you have that like have like the expert in everything and then what comes out? Like you tend to learn so many things that like, by the way, it turns into this rabbit hole. And I noticed that my prompt actually, ’cause I always tell it to me, like, explain it to me, me like I’m 16. So I’ve been driving into this other thing of, it’s been teach me about quantum entanglement. Are you familiar with this? Of course. Well, like

[01:02:29] Barry Ritholtz: Who isn’t familiar with spooky action at a distance? I mean, they teach that in middle school. Yeah,

[01:02:35] Jeff Chang: Exactly. So the, the quantum entanglement of that, you have two protons that, you know, if you do want to XY we’ll do the same. It’s just like having two dice if dice on Earth, by the way, they’ve proven this, like if you roll the, the, the dice on earth, it rolls a six. It’ll definitely roll a six. And it’s not bound by space and time. So basically it could be light years away, you roll that dice, it rolls an eight, this one in earth is gonna roll an eight. And so then they sort of combine that with is that part of human consciousness that is your consciousness. Quantum entangled is what makes

[01:03:10] Barry Ritholtz: You, you

[01:03:11] Jeff Chang: By the way this type of like thinking, there’s,

[01:03:13] Barry Ritholtz: There’s a related topic, and I haven’t run this through chat GBT, but I should, which is the concept of emergence. Yeah. Intelligence emergence as the natural outcome of the universe. Why does the universe exist if not to create a conscience Yeah. Intelligence or, although the flip side of that is life is fairly common throughout the universe. Hydrogen, carbon, oxygen, nitrogen. But advanced technological life so far at least appears to be exceedingly rare. Yeah. So that’s the counterbalance of totally. Of emergence. Totally. But,

[01:03:52] Jeff Chang: And then the other thing that I found recently that people can dig into, I think this is fascinating, is that your head experiences time different than your feet from the proximity of gravity’s.

[01:04:05] Barry Ritholtz: Well certainly we have to adjust GPS Yeah, yeah. Because the, for the relative relative relativity Yeah.

[01:04:11] Jeff Chang: The GPS versus

[01:04:12] Barry Ritholtz: Which, which Einstein turned out to be Right. About that. Exactly. So, but the difference between your head and feet Oh yes. Is so tiny. Unless yes, you’re falling into a black hole and then spaghettification So is is the problem.

[01:04:24] Jeff Chang: Yeah. So then you take quantum entanglement and you then say, okay, if I have a proton here and a proton elsewhere, and the light and the how that proton experience is time through entanglement versus how time bends with gravity. By the way, all of this just keeps going deeper and deeper and deeper on the rabbit. And then, and then the thing is, is that I keep telling it to explain it to me like I’m 16 now. My entire prompt explains everything. I will explain it to you as if you’re 16 years old.

[01:04:57] Barry Ritholtz: So the, the issue I occasionally run into Yeah. With perplexity or, or Chachi pt, is it tends to conform its output to you. Yes. And sometimes I’ll ask a question and it’s like, no, I don’t want a list of 10 podcast questions. Yes. I just tell me about Jeff Chang and what led to vest. Don’t gimme a podcast. That’s right. I I have my own

[01:05:20] Jeff Chang: Questions. That’s why I use multiple gr everything else. Right. That, that way I get a, a whole plethora. And then what ends up happening is you get all this new stuff and then you dig deep into whatever topic. And I found that so fascinating because I just, it’s curiosity. It’s like it’s

[01:05:37] Barry Ritholtz: Continue if you’re interested in these sorts of things. Exactly.

[01:05:39] Jeff Chang: Absolutely. And, and

[01:05:41] Barry Ritholtz: By the way, but you have to be on guard for the occasional hallucination. Oh, a hundred percent. And every now and then I find myself leaving AI to go to just traditional search. Yeah. And say, Hey, show me a source for this. Is is this? Yeah. I, I don’t think before ai I don’t think people were skeptical enough about the sources of what they consumed with ai. Yeah. You really have to know what is real and what is fake. That’s right. People, people missed that. All right. Our final two questions. What sort of advice would you give to a recent college grad interested in a career in asset management? Or, or, or gen or ETFs specifically?

[01:06:22] Jeff Chang: Yeah. I think a recent college grad. I think similar to kind of bringing it full circle, same thing. Like develop the skills that, you know, you’re not beholden to anybody. Right. Whatever that is. Whether you’re in college or outta college. Like, develop those skills that you can actually, that they’re portable, one to the other. And then not be afraid of failure. Take chances. Now, this is not for everybody. I would say, you know, meaning not everybody is going to be a founder. Not everybody’s gonna be an entrepreneur, which I, by the way, I find as two different people. Founder has the creativity. An entrepreneur has the grit and influence. A founder has to have the creativity. ’cause you’re, you’re actually introducing a whole new industry or a whole new thing that somebody else has not seen yet. Right. But that’s the thing. And then also keep your eye out for painful problems that you have the skillset to solve. So obtain those skill sets and then have your eyes out, eyes peeled throughout life. Write them down.

[01:07:29] Barry Ritholtz: Look for pain points,

[01:07:31] Jeff Chang: Look for pain points, look for problems. And then the second, the last thing is just a personal thing is don’t take yourself too seriously. Right. Have fun with life. And, and I think that, that, that is, ’cause otherwise all this stuff can create massive amounts of burnout.

[01:07:46] Barry Ritholtz: And our, our final question, what do you know about the world of buffered funds investing ETFs today might have been healthful 15, 20 years ago when you were first getting started,

[01:07:59] Jeff Chang: How hard it would’ve been, right. Like literally,

[01:08:03] Barry Ritholtz: Would that have discouraged you from launching or, yes.

[01:08:06] Jeff Chang: I think that was actually the superpower, right? Like when you climb a mountain and you don’t know how high it is and there’s a cloud base, if you saw and a clear view, it, it probably wouldn’t be, if you told me to quit my job and I wouldn’t get paid for four plus years, I probably wouldn’t have done that. But then it’s like always success is always around the corner. At least you dream of it, right? Everybody sees what you are now. They don’t see the pain where you’re constantly just waiting for that cloud to clear on the next part of the mountain. Because I, I could tell you this, that like, if, if, if you saw the how big the mountain is, it would be nobody would do it. Huh.

[01:08:43] Barry Ritholtz: Really, really interesting. Yeah. Thank you Jeff for being so generous with your time. We have been speaking with Jeff Chang, co-founder and president of Vest. If you enjoy this conversation, well check out any of the 600 we’ve done over the past 12 years. You can find those at iTunes, Spotify, YouTube, Bloomberg, wherever you get your favorite podcasts. I would be remiss if I didn’t thank the Croc staff that helps put these conversations together each week. Alexis Noriega is my video producer. Sean Russo is my researcher. Anna Luke is my podcast producer. I’m Barry Ritholtz. You’ve been listening to Masters in Business on Bloomberg Radio.

~~~

The post Transcript: MiB: Jeff Chang, President and Co-Founder of Vest appeared first on The Big Picture.

Recent comments