Futures At Session Highs After Oil Drops Below $100 On India Hormuz Transit Hopes

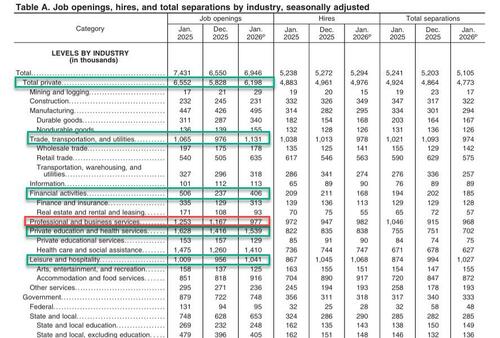

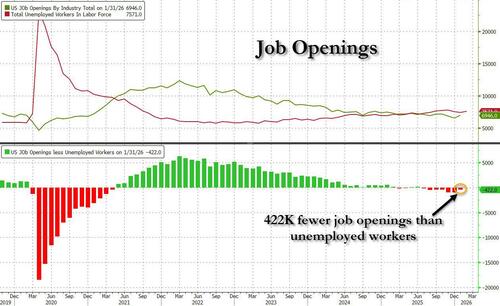

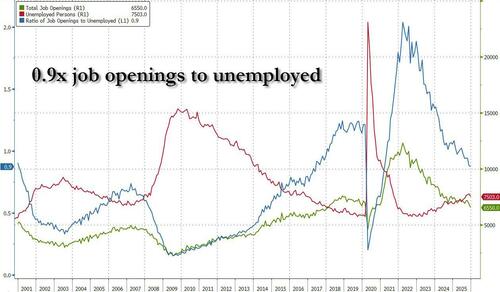

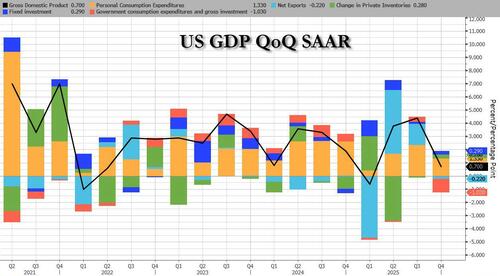

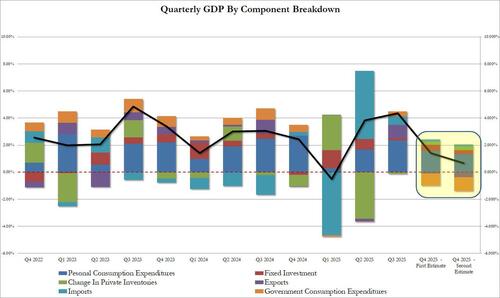

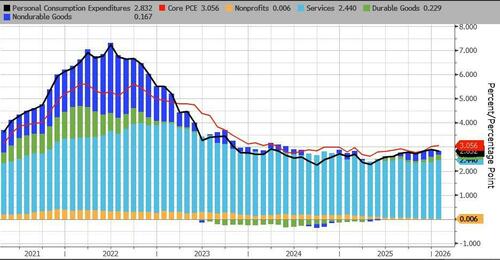

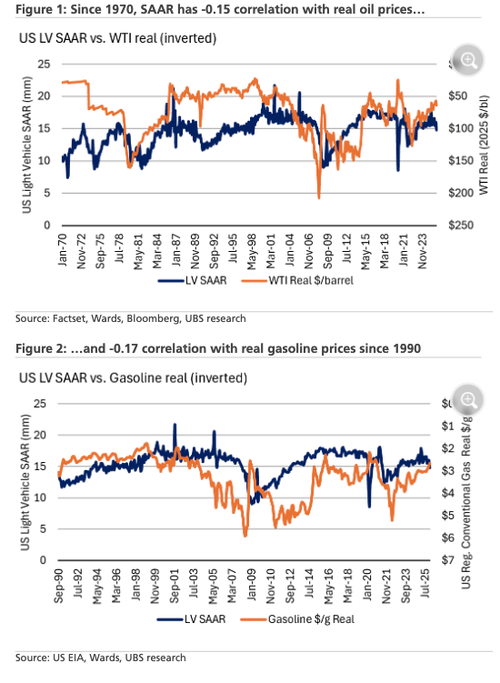

US stock futures rebounded from their overnight selloff, and were trading near session highs after three days of losses on Wall Street as Brent slipped below $100 a barrel and investors waited to see if the war in the Middle East would escalate further. The catalyst for the bounce was news that India asked Iran to allow its tanker armada through Hormuz, which would lead to a substantial easing of the global oil shipping blockade. And while it remains to be seen if this will pave the way for other flows through the strait, for now futures have rebounded with Emini S&P futures up 0.3% at 6700 and Nasdaq futures rising 0.4%; in premarket trading Mag 7 stocks are flattish except for the -1.4% decline in META after it delayed the rollout of its new frontier model “Avocado.” Bond yields reverse an earlier rise and were flat higher this morning while the USD is 0.4% higher, with DXY now reaching above 100. Oil prices drop overnight with WTI trading around $93 after India stated it has an oil tanker moving out of the Strait of Hormuz. Other commodities are mixed: Aluminum added 1.7%, Silver fell -1.0% this morning. US economic data slate includes January personal income/spending, PCE price index, durable goods orders, 4Q second GDP estimate (8:30am), March University of Michigan sentiment, January JOLTS job openings (10am).

In premarket trading, Magnificent Seven are mixed (Tesla +0.9%, Alphabet +0.9%, Nvidia +0.8%, Apple +0.3%, Amazon +0.3%, Microsoft +0.1%, Meta Platforms (META) -1%)

- Adobe (ADBE) falls 7% as Chief Executive Officer Shantanu Narayen will resign from his position amid deep skepticism about the company’s ability to thrive in the AI era.

- EverCommerce Inc. (EVCM) drops 21% after the management software firm reported adjusted earnings per share for the fourth quarter that missed the average analyst estimate.

- KinderCare Learning Cos. (KLC) declines 31% after the childhood education company provided a disappointing 2026 earnings outlook.

- Klarna Group (KLAR) rises 7% after the fintech’s chairman bought 3.47 million shares worth about $50 million between March 3 and March 11.

- ServiceTitan (TTAN) falls 5% as the software company reported fourth quarter results. Bloomberg Intelligence says the results ran up against high expectations.

- Once Upon a Farm PBC (OFRM) drops 14% after the organic kids snacks maker forecast slowing sales growth in 2026 in its first earnings report as a public company.

- PagerDuty (PD) falls 12% after the software company gave a revenue forecast that’s weaker than expected.

- PAR Technology (PAR) falls 22% after pricing a private offering of $250 million aggregate principal amount of 4% convertible senior notes.

- SentinelOne (S) falls 4% after the software company’s outlook was seen as unimpressive.

- Ulta Beauty (ULTA) drops 7% after the cosmetics retailer offered guidance for the current year that was toward the low end of Wall Street’s expectations.

In corporate news, Adobe shares fell more than 8% in premarket trading after the maker of software for creative professionals delivered a lackluster forecast and announced its long-standing CEO Shantanu Narayen would step down amid deep skepticism about the company’s ability to thrive in the AI era. And Apple is lowering the fees it collects from app developers in China, a major concession in a hugely lucrative market where

Nearly two weeks into the war in the Middle East, investors are struggling to find havens as bonds fall alongside equities and hopes for further policy easing fade while stagflation risks mount. There were a few new articles on Iran, pointing to the oscillating narrative between US off-ramp and the closure of the Strait. A global equity index was set for a second week of losses, having fallen from record highs hit before the conflict. A key sentiment indicator compiled by Bank of America Corp. showed the recent selloff hasn’t yet created conditions for investors to buy beaten-down securities.

“Markets have sailed through the last quarter with an optimistic bias, sticking to a buy-the-dip mantra, but this spike in volatility is likely to put an end to this,” said Benoit Peloille, chief investment officer at Natixis Wealth Management. He added that even if the conflict doesn’t last much longer, “it may already have a palpable negative impact on economic growth and inflation.”

Oil prices are now more than 60% higher than at the start of 2026, shrugging off coordinated moves by wealthy nations to release crude reserves and temporary US waivers allowing purchases of Russian oil. Crude could exceed the 2008 peak close to $150 a barrel, should flows via the Strait of Hormuz remain depressed through March, Goldman Sachs Group Inc. warned.

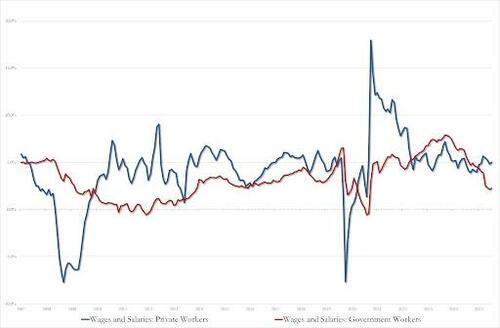

As energy price pressures build, the risk of an inflation shock is trumping the traditional appeal of bonds as a haven. Treasuries volatility jumped to a nine-month high, yields are marching higher across the curve and markets are no longer fully pricing in even one quarter-point rate cut by the Fed this year. Higher yields are exacerbating already elevated concern about stress in the private credit market, hurting risk appetite generally and the banking sector specifically.

Investors will turn their attention to US inflation figures due later Friday. The Federal Reserve’s favored price gauge is expected to show inflation remaining stubbornly high. Meanwhile a preliminary March survey will show how American consumers view the impact of the Iran conflict, given the rise in gasoline prices.

“Inflation is actually ramping up as a big risk,” Tracy Chen, a portfolio manager for global fixed income at Brandywine Global Investment Management, said on Bloomberg Television. “Duration of the conflict is key. We have been raising US dollar weighting a little bit just to increase our hedge.

European stocks are off well their worst levels, with the Stoxx 600 almost back to flat for the day having lost over 1% at the lows. A pullback in energy prices helped with European natural gas futures falling more than 1%. BE Semiconductor is the day’s most significant outperformer, after reports about takeover interest. Here are the biggest movers Friday:

- BE Semiconductor shares surge as much as 14% in early Friday trading after Reuters reported that the semiconductor equipment firm has been fielding takeover interest

- Zalando rises as much as 6.4%, building on yesterday’s result-driven gains and trading at a five-week high, after being upgraded at Bernstein. Analysts believe the risk-reward profile is more balanced

- Worldline shares gain as much as 46% after the payments company launched a capital increase. Heavily targeted by short sellers, the stock gets a boost when shareholders participating in the rights offering recall the shares back

- Siltronic shares rise as much as 3.3%, building on Thursday’s gains after the silicon wafer manufacturer reported results. Analysts at Oddo BHF raised their price target on the stock this morning as well

- Medacta climbs as much as 6.5%, the most since the end of July, after the Swiss medical-implant firm reported its full-year results and raised guidance

- Webuild drops as much as 6% after BNP Paribas downgraded the stock to neutral from outperform, citing the Italian construction company’s outlook for flat sales in 2026 along with slower growth in the Middle East

- ID Logistics shares drop as much as 9.7%, extending yesterday’s result-driven losses and slumping to a fresh 11-month low. TP ICAP trimmed its target price on the stock this morning

Hours after Deutsche Bank flagged a €26 billion ($30 billion) exposure to private credit on Thursday, the head of structured credit at Dan Loeb’s Third Point said the hedge fund is readying to scoop up credit assets others are selling to raise liquidity. “This is probably one of the most exciting times to be a credit investor,” Shalini Sriram said on the latest Bloomberg Intelligence Credit Edge podcast.

Earlier in the session, Asian stocks fell on Friday, notching a second-consecutive weekly decline as the Iran war stokes concerns of elevated oil prices and the impact on inflation. The MSCI Asia Pacific Index slid as much as 1.4% Friday, with chipmakers TSMC, Samsung and SK Hynix the biggest drags. India and South Korea led a broad regional decline, while Indonesia’s benchmark entered a bear market.

Investors remain concerned about tight energy supply, with oil trading above $100 a barrel. A prolonged war could hobble manufacturing and drive up costs, and faster inflation may drive more hawkish monetary policy.

In FX, the Bloomberg Dollar Spot Index rises 0.4% to a year-to-date high. The pound is among the weakest of the G-10 currencies, falling 0.6% against the greenback after the UK economy unexpectedly failed to grow in January. The yen is flat having earlier dropped to its lowest since July 2024.

In rates, Treasury futures ticked higher as oil prices dipped in early US session after India said it had an oil tanker that has started moving through the Strait of Hormuz. Yields flipped to slightly richer on the day across front and belly of the curve, ahead of a day packed with US data including GDP, PCE and JOLTS job openings. US yields richer by around 1.5bp across front and belly of the curve, slightly cheaper across the long-end, steepening 2s10s and 5s30s spreads by 1.5bp and 2bp on the day, unwinding a small portion of Thursday’s aggressive flattening move as Fed rate cut premium eroded from the front-end of the curve. European government bonds also recovered as traders trimmed bets on tightening by the European Central Bank and Bank of England this year. UK and German 10-year borrowing costs are flat. US 10-year yields rise 1 bp to 4.27%.

In commodities, WTI futures lower on the day by around 2%, dropping following the India headline, after rising as high as $98 a barrel on Friday after a 9.7% jump on Thursday as defiant tones from Trump and Iran’s new leader Mojtaba Khamenei drained optimism about any swift resolution to the conflict. Betting on Polymarket puts the chance of a ceasefire by the end of the month at just 21%. Spot gold edges higher while silver drops over 1%. Bitcoin climbs 3%.

Today's US economic data slate includes January personal income/spending, PCE price index, durable goods orders, 4Q second GDP estimate (8:30am), March University of Michigan sentiment, January JOLTS job openings (10am)

Market Snapshot

- S&P 500 mini +0.3%

- Nasdaq 100 mini +0.4%,

- Russell 2000 mini +0.3%

- Stoxx Europe 600 -0.2%,

- DAX -0.5%,

- CAC 40 -0.6%

- 10-year Treasury yield unch basis point at 4.26%

- VIX -0.3 points at 27.02

- Bloomberg Dollar Index +0.3% at 1213.01,

- euro -0.5% at $1.1456

- WTI crude little changed at $95.76/barrel

Top Overnight News

- Arab diplomats trying to find a diplomatic path out of the war now being waged by the U.S. and Israel against Iran say Tehran, emboldened by its ability to rattle the global economy by choking oil shipments, has laid out steep preconditions for any return to talks. WSJ

- Iran has started laying mines in Hormuz and is utilizing thousands of small boats in the country’s navy to do so. NYT

- Israeli officials now assess that Iran’s ruling regime is unlikely to fall in the immediate future, as Tehran’s battered rulers remain in control and conditions on the ground aren’t yet ripe for a popular uprising, people familiar with the matter said. WSJ

- Donald Trump warned Iran to “watch what happens” today in a social media post, claiming the US is “totally destroying” Iran militarily and economically. Benjamin Netanyahu said regime change can’t happen without an internal uprising. BBG

- The US expanded a short-term waiver allowing buyers to purchase Russian oil already in transit, potentially freeing up about 19 million barrels of crude and refined products in Asian waters. BBG

- The framework for US President Donald Trump’s summit with China’s Xi Jinping is set to be mapped out this weekend as negotiators meet to discuss thorny issues such as tariffs, fentanyl and Taiwan. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, US Trade Representative Jamieson Greer and China’s Vice Premier He Lifeng will convene in Paris on Sunday and Monday to map out deliverables for the leaders’ summit slated for March 31 to April 2 in Beijing. BBG

- US Secretary of State Rubio will join US President Trump during his trip to China later this month.

- TikTok’s Chinese parent, ByteDance, is assembling computing power with high-end Nvidia chips outside China to fuel its ambition of becoming a global artificial-intelligence leader. WSJ

- India is delaying signing a deal with the US for several months after new investigations, Reuters reported. New Delhi had originally aimed to finalize an interim deal this month. BBG

- Adobe CEO Shantanu Narayen is stepping down after 18 years amid concerns about the company’s ability to compete in AI. Shares are down -8% in the premkt. BBG

A more detailed look at global markets courtesy of Newsquawk

APAC stocks were mostly subdued with the region cautious amid headwinds from the recent double-digit surge in oil prices after Iran's new Supreme Leader dug in and called for a continued closure of the Strait of Hormuz, as well as warned that other fronts will be opened if the war persists, while the US also initiated 60 Section 301 investigations related to failures to take action on forced labour. ASX 200 traded indecisively as strength in financials and energy offset the losses in mining and materials. Nikkei 225 underperformed as oil and inflationary-related pressures weighed on the large exporting industries, including tech and autos, with Honda among the worst hit after it cancelled three planned EV launches in North America and revised its FY25/26 outlook to a loss of as much as JPY 690bln from the previous guidance of JPY 300bln profit. Hang Seng and Shanghai Comp were lacklustre in rangebound trade with a lack of conviction heading into talks between US Treasury Secretary Bessent, USTR Greer and Chinese Vice Premier He Lifeng in Paris beginning on Sunday.

Top Asian News

- Japanese Finance Minister Katayama said prepared to take all necessary steps on FX and are in closer contact with US authorities on FX.

- South Korea could reportedly see KRW 20tln extra budget on chip boom, according to Chosun.

European bourses (STOXX 600 -0.2%) continue to trade on the softer side as energy prices remain at elevated levels. Once again, the IBEX 35 (-0.2%) is the worst performer as Banks continue to weigh on the index. The FTSE 100 (-0.1%) is also under modest pressure, after the UK showed no growth M/M in January. European sectors are mixed, with Energy (+0.8%) outperforming as Brent holds above USD 100/bbl. Basic Resources (-1.2%) lags as the stronger dollar weighs on metals prices. Consumer Products and Services (-1.4%) and Banks (-0.7%) are also underperforming as higher inflation expectations and poor growth prospects weigh on the sectors. For the semiconductor space, BE Semiconductor has reportedly been fielding takeover interests and has refused to respond to the rumour.

Top European News

- UK GDP YoY (Jan) Y/Y 0.8% vs. Exp. 0.9% (Prev. 0.7%, Low. 0.8%, High. 1.0%).

- UK GDP MoM (Jan) M/M 0.0% vs. Exp. 0.2% (Prev. 0.1%, Low. 0.1%, High. 0.3%).

- UK Balance of Trade (Jan) 3.922B vs. Exp. -6.2B (Prev. -4.340B).

- UK Goods Trade Balance (Jan) -14.45B vs. Exp. -22.2B (Prev. -22.72B, Low. -23.3B, High. -21.2B).

FX

- DXY is stronger this morning and currently just off best levels, within a 99.58-100.29 range; upside today lacked a fresh fundamental driver, but came alongside the strength in crude prices, where Brent once again topped USD 100/bbl. Interestingly, the USD-Brent correlation is currently 0.91. On the oil situation, the US issued a new Russia-related general licence permitting the sale of Russian crude oil – this only applies to oil in transit. A waiver which did little to cull the upside in the oil complex, given this does not nearly replace the lost supply from the Gulf. ING writes that “we cannot see investors wanting to fight this dollar rally, given there is so little certainty as to when this crisis will end”. Focus now turns to Core PCE Price Index (Jan), Durable Goods Orders (Jan), Personal Spending (Jan), JOLTS (Jan), University of Michigan Consumer Sentiment Prelim. (Mar) and Atlanta Fed GDP.

- EUR has now sunk below the 1.1500 mark, and made a trough at 1.1433 – levels not seen since early August, where the single currency made a low at 1.1391 (1 Aug). Ultimately, the region's status as a net-importer of oil continues to weigh on the single currency. In the meantime, focus will be on any hints of government intervention to ease the impact of higher energy costs, before focus then turns to the ECB next week, where the Bank is likely to raise concerns about the Middle East situation, with an outside chance that it signals possible policy adjustments.

- GBP also remains pressured alongside peers. Sterling opened lower, given the USD strength, but then reacted negatively to the region’s GDP metrics, which showed that the UK stagnated in January, even before the Iran war started. Cable fell from 1.3315 to 1.3306 within a couple of minutes, before trundling lower as the USD strength picked up. The impact on the BoE following this data will likely not be impactful on policy in the near term, given the Iran war.

- JPY remains the only G10 flat vs USD. Potentially a function of traders seeing the possibility of near-term intervention/rate checks as USD/JPY sits firmly in the intervention zone, beyond 158.00. Overnight, Finance Minister Katayama said that they are in closer contact with US authorities on FX, and separately commented that they are prepared to take all necessary steps on FX. As a reminder, the NY Fed conducted a rate check on USD/JPY back in January. As mentioned previously, intervention seems unlikely given a) it would prove to be ineffective given the current geopolitical environment, b) low volume short positions on the JPY, c) the move is fundamentally driven by higher energy prices, and d) the recent lack of verbal intervention suggests potentially a higher bar for USD/JPY to rise. Nonetheless, markets will be cognizant of any jawboning heading into the BoJ meeting and wage negotiations next week.

Trade/Tariffs

- USTR confirms to start 60 Section 301 investigations related to failures to take action on forced labour.

- China's MOFCOM said US 301 tariffs violate WTO rules, urges the US to correct wrong practices and return to dialogue. China is analysing and assessing the situation. Will take necessary measures to safeguard legitimate rights and interests.

- China's MOFCOM is to impose tariffs of up to 30.1% on imports of rubber from Japan and Canada, effective March 14th.

- US ambassador to India said they're moving to a critical stage of finalising critical minerals agreement, adds expect countries we have made deals with to honor those deals.

Fixed Income

- A choppy start to the day with benchmarks in narrower ranges than usual, though still posting a c. 50 ticks band for Bunds, for instance. Action this morning has largely been a function of energy and, by extension, the general risk tone. A grind higher in the first few hours in energy benchmarks to a USD 98.09/bbl peak for WTI sparked a bout of fixed downside, equity pressure and USD strength.

- However, the move in fixed income has pared with benchmarks marginally firmer as energy wanes from best. The main headline update amidst this was Axios reporting that US President Trump told the G7 on Wednesday that Iran was close to surrender; however, commentary from the new Supreme Leader on Thursday and Iran announcing a fresh wave of attacks today somewhat disputes that assessment.

- Specifically, USTs in a 111-12 to 111-20 band, currently firmer by a tick or two in that. Nonetheless, the benchmark is set to end the week lower by around a full point.

- For Bunds, they are yet to make a lasting move into the green, despite hitting a 126.18 peak with gains of two ticks briefly. Drivers much the same as above. Furthermore, the benchmark is also set to end the week lower by around a full point.

- Finally, Gilts opened lower by just under 20 ticks today before slipping to a 88.49 low and then rebounding to near-enough unchanged. Downside a function of the benchmark catching up to post-close action and the morning's initial energy move. However, this was somewhat offset by the morning's data showing the UK started the year with no growth. A series that may have otherwise cemented a March cut by the BoE. However, the recent Middle East related energy disruption and associated moves mean a near-term cut is entirely off the table, though the MPC will likely remain divided next week in another split decision.

- Japan sold JPY 300bln in 10yr Climate Transition Bonds b/c 3.42 (Prev. 3.56).

Commodities

- WTI and Brent futures are off their best and worst levels at the time of writing, with traders gearing up for another week of geopolitical risks as the war shows no signs of abating. It was reported that the US issued a second short-term waiver allowing buyers to receive Russian oil already at sea, expanding a previous India-only authorisation without materially benefiting the Russian government. Modest downticks were seen in the complex following an Axios report that US President Trump told G7 leaders in a virtual meeting Wednesday that Iran is "about to surrender," according to three officials from G7 countries briefed on the contents of the call, although the report caveats that 24 hours later after that call, Iran's new supreme leader issued his first public statement vowing to keep fighting. WTI resides in a USD 94.52-98.09/bbl range and Brent in a 99.51-102.75/bbl range. Nat Gas prices are flat at the time of writing, but remain above EUR 50/MWh amid the ongoing energy woes emerging from the Iranian crisis.

- Spot gold rose above USD 5,100/oz overnight and hovers on either side of the figure in recent trade, but still remains on track for a second weekly decline, as the Middle East conflict keeps oil near USD 100/bbl and in turn pushes up the USD (DXY north of 100) amid inflationary woes. Spot gold resides in a USD 5,061.32-5,128.47/oz. Spot silver resides closer to weekly lows after finding resistance at USD 90/oz on Tuesday.

- In terms of base metals, 3M LME copper is on a softer footing amid the firmer USD and with sentiment also dampened as the US opened a Section 301 probe into forced-labour practices across 60 economies, including the EU, China, Japan, South Korea, Canada, Mexico, India, Taiwan and the UK. Iron is set for its biggest weekly gain in more than a year after China state-backed buyers expanded restrictions on BHP Group (BHP AT) products.

- India asks Iran to allow tankers through the Strait of Hormuz, according to the WSJ; India is in active talks to allow 23 tankers through the Strait, with first crossing expected this weekend

- Kremlin envoy Dmitriev said US sanctions waiver affects around 100mln barrels of Russian oil.

- US has issued a new Russia-related general license permitting the sale of Russian crude oil and petroleum products loaded on vessels as of March 12, according to the Treasury website. US license permits sale of such Russian crude oil and petroleum products until 12:01 AM EDT on April 11th.

- US Treasury Secretary Bessent clarified that new general licence applies only to Russian oil already in transit and will not provide significant financial benefit to the Russian government.

- EU Commission said gas storage filling levels in the EU remain stable and oil stocks are at a high level, via statement; gas storage should not be refilled at all costs.

- Japan's Defence Minister Koizumi said it would be possible to provide escort for Japanese ships through Hormuz, however PM Takaichi clarified that no decisions have been made.

- Saudi Aramco offers to sell 2 mln barrels of Arab Light crude for March loading at Yanbu port.

- Australia's energy minister announces lowering minimum stock obligations for diesel and fuel. said: To address fuel supply chain disruption by reducing up to 20% of the baseline minimum stockholding obligation for petrol and diesel, which would allow the release of up to 762mln litre of petrol and diesel from Australia's domestic reserves.

- Venezuela and Repsol (REP SM) signed strategic agreements, while Venezuela's interim president Rodriguez said that the deal can make Venezuela a gas exporter.

- Rio Tinto (RIO AT) suspends all mining operations at its Kennecott copper facility following a fatal incident.

- Goldman Sachs expects Brent crude prices to average over USD 100/bbl in March and USD 85/bbl in April, while it sees Brent crude gradually easing back to the low USD 70s late in the year.

Geopolitics

- NATO intercepts an Iranian missile targeting Turkey, the 3rd occasion since the Middle East conflict began. Missile was launched from Iran and destroyed by defences in the eastern Mediterranean.

- US President Trump told G7 leaders in a virtual meeting Wednesday that Iran is "about to surrender," according to three officials from G7 countries briefed on the contents of the call, Axios reported.

- US has burned through ‘years’ of munitions since the Iran war began, while the rapid depletion of stockpile including Tomahawk missiles raises pressure on US President Trump regarding the cost of the war, according to FT.

- US officials say Iran has begun laying mines in the Strait of Hormuz as of today, according to NYT.

- US Treasury Secretary Bessent said we know that Iran has not mined the Strait of Hormuz, noted a lower oil price regime over the medium-term after the conflict.

- US weapons package for Taiwan could be approved after US President Trump's China trip, according to sources.

- Israeli Security Official said that Iran has around 150 missile launch platforms, these will continue to be targeted.

- Israeli army said it has begun a wave of air strikes targeting government infrastructure in Iran’s capital, Tehran, Al Jazeera reported.

- Israeli air strikes are underway in Iran and explosions were reported in Tehran.

- Israel's army identified missiles launched from Iran and defence systems were activated to counter threat.

- Israel conducts a series of raids on southern suburbs of Beirut.

- Israeli army issues orders to evacuate areas in the southern suburbs of Beirut, Sky News Arabia reported.

- Iran announces a fresh wave of attacks on US bases and Israel, ISNA reported.

- "Iranian state television reported a large explosion in a Tehran square where demonstrations are happening", via AP's Gambrell.

- Iranian missile successfully hits target after Israeli interceptors failed to stop it.

- Iran claims responsibility for shooting down US refueling plane, said US refueling plane was downed with all crew killed in Western Iraq, according to Tasnim.

US event calendar

- US economic data slate includes January personal income/spending, PCE price index, durable goods orders, 4Q second GDP estimate (8:30am), March University of Michigan sentiment, January JOLTS job openings (10am)

DB's Jim Reid concludes the overnight wrap

Without putting too much of a downer on things, today marks the first occurrence of successive monthly Friday the 13ths since 2015. Thanks to a client with an impressive archive, I was sent the EMR from the last time I commented on this—11 years ago today. I wouldn't have known otherwise. The next back-to-back Friday the 13th doesn’t arrive until March 2037. I have mixed feelings about whether I’d like to still be writing about that particular statistic when it comes around again, especially as the EMR will be exactly 30 years old at that point.

Perhaps back-to-back Friday the 13ths will reverse the usual superstition and bring a bit of luck instead—something markets could certainly use when conditions are becoming ever more fraught. The challenge for investors is that a sharp turnaround could materialise at almost any point if both sides de escalated. There are obvious incentives to do so. However, there are currently no signs that such an outcome is imminent. Our house view, articulated by Helen Belopolsky in my team, is that events are likely to get worse before they get better, although de escalation remains plausible at some point over the next few weeks.

Over the past 24 hours, we’ve seen another round of escalatory rhetoric from both sides, which pushed Brent crude (+9.22%) back up to $100.46/bbl, the first time it’s closed above $100/bbl since August 2022. We’re still hovering around those levels overnight, with Brent at $100.11/bbl this morning. While it remains feasible that the most intense phase of the conflict ends relatively quickly, concerns are clearly growing that this will turn into a much more prolonged confrontation. Indeed, that uncertainty reignited inflation fears yesterday, leading to the most hawkish central bank pricing of the year so far for both the ECB and the Fed. Sovereign bonds sold off again, with 10yr bund yields (+2.5bps) reaching a post 2023 high of 2.95%. And in turn, those geopolitical concerns and expectations of a more hawkish policy response triggered a fresh equity sell off, with the S&P 500 (-1.52%) falling to its lowest level since November. By contrast, the dollar index (+0.51%) reached its highest level since November.

In terms of the latest, the harsh rhetoric continued yesterday, alongside the first public comments from Iran’s new Supreme Leader Khamenei. He said the Strait of Hormuz should remain shut and warned that, if the war persisted, other fronts would be opened. Meanwhile, President Trump posted that preventing Iran from acquiring nuclear weapons was “of far greater interest and importance to me” than oil prices. And in the last couple of hours, Trump has posted that we should “watch what happens” to Iran today. There were also conflicting reports about mines in the Strait of Hormuz, with UK Defence Secretary Healey cautioning that “the Iranians may have started mining in the strait”. However, US Treasury Secretary Bessent claimed “we know that they have not mined the straits” as some tankers are coming through. Meanwhile, US Energy Secretary Wright suggested that the US could start escorting tankers through the strait by the end of March.

With no sign of an imminent resolution, oil prices posted significant gains yesterday. Brent crude (+9.22%) rose to $100.46/bbl, while WTI (+9.72%) climbed to $95.73/bbl. And even though this is still well below Brent’s intraday high of $119.50/bbl right after the weekend, the longer prices hover around $100/bbl, the greater the risk of serious inflationary consequences. That’s been reflected in expectations, as the 1yr Euro inflation swap jumped +19bps yesterday to 2.96%, its highest level since late 2023. Moreover, investors are also pricing a longer period of elevated energy prices, with the 12-month Brent future (+2.67%) rising to $76.15/bbl, with a further move up to $76.68/bbl overnight.

Those oil price gains came even as the US has looked to introduce additional measures in response to the energy shock. For instance, Bloomberg reported that the administration plans to waive the Jones Act, which requires shipping between US ports to be done by American ships. So that could reduce costs for shipping fuel within the US and helped a modest decline in US crack spreads yesterday (the difference between crude oil and wholesale petroleum). Then in the evening, the US Treasury announced an expansion of temporary sanction waivers for purchases of Russian oil.

Beyond commodities, sovereign bonds saw another broad sell off as inflation fears fed into renewed rate hike speculation. The move was especially clear in Europe, where 10yr bund yields (+2.5bps) rose to 2.95%, their highest level since October 2023. France’s 10yr OAT yield (+5.6bps) climbed to 3.62%, its highest since the peak of the Euro crisis in 2011. UK gilts fared even worse, as market pricing for a BoE rate hike this year hit an 82% probability by the close, with the 10yr gilt yield (+8.7bps) closing at a six-month high of 4.77%.

US Treasuries followed a similar pattern, with particularly pronounced increases at the front-end as doubts grew about the Fed’s ability to cut rates this year, even under a new Chair. So there are now just 20bps of cuts priced in by the December meeting, meaning that—for the first time this year—a 2026 rate cut is no longer fully priced. Instead, investors have to look as far out as the June 2027 meeting for the first fully priced cut. That backdrop drove another sell off, with the 2yr Treasury yield (+9.0bps) rising to a six-month high of 3.74%, while the 10yr yield (+3.1bps) moved up to 4.26%.

That combination of higher oil prices and more hawkish central bank pricing weighed further on risk assets, with equities declining on both sides of the Atlantic. The S&P 500 (-1.52%) fell for a third consecutive session, reaching its lowest level since November. Yet even so, the index is still only -4.4% off its record high and -3% below its pre strike level. So despite the volatility, it’s still not halfway to technical correction territory, let alone a bear market. Energy stocks (+0.98%) outperformed, with that segment of the S&P 500 reaching a record high. Meanwhile in Europe, the STOXX 600 (-0.61%) fell for a second day, though it remains above Monday’s levels and is still -5.5% below its prestrike record high, again some distance from correction territory.

That said, the equity performance was increasingly challenging yesterday, with 391 decliners in the S&P 500, the most since January. The Mag-7 (-1.86%) snapped a three-day winning streak, moving to within half a percent of technical correction territory, while the small cap Russell 2000 (-2.12%) closed at a 2026 low. In addition to the oil spike, market sentiment was weighed on by renewed concerns over private credit, the S&P 500 Banks (-2.16%) underperforming the broader index, whilst US IG credit spreads widened +4bps to 90bps, their highest level since May.

Overnight in Asia, that slide has continued for the most part, with sizeable losses for the Nikkei (-1.37%) and the KOSPI (-1.76%). Chinese equities are faring relatively better however, with the CSI 300 (+0.36%) and the Shanghai Comp (+0.02%) posting modest gains. In the meantime, the Japanese yen has weakened further in the last 24 hours, closing at 159.35 per US Dollar yesterday, the weakest since July 2024. Indeed, it’s getting closer to levels where the authorities have previously intervened to support the currency. Looking forward however, equity futures in the US and Europe are a bit more positive this morning as oil prices have been relatively stable in the last 24 hours. So those on the S&P 500 are up +0.17%, and those on the DAX are up +0.13%.

Looking ahead, today’s data releases include UK GDP and Euro Area industrial production for January. In the US, we’ll also see January PCE inflation, the second estimate of Q4 GDP, and preliminary durable goods orders for January. Central bank speakers include the ECB’s Wunsch.

Tyler Durden

Fri, 03/13/2026 - 08:34

Source: Yeni Safak

Source: Yeni Safak

Recent comments